saving Abu Simbel temple

saving Abu Simbel temple is one of the largest and most magnificent monuments of the ancient world.

It is also an unusual one in not being a free-standing temple; its inner chambers were hewn out of the heart of a mountain.

Aware that the building of the High Dam would result in the total inundation of the site, Egypt decided to seek international assistance.

The government officially appealed to UNESCO for assistance in 1959.

It explained that once construction was started on the High Dam at the beginning of the coming year, the water in the reservoir would start to build up.

It would then be a race against time to saving Abu Simbel temple before the summer of 1964, the expected date of completion.

The Egyptian government explained that Egypt did not have the necessary expertise and asked for help.

UNEsco was positive in its response.

An international appeal was launched to saving Abu Simbel temple and other ancient monuments in Nubia. Different countries offered technical and financial aid for the saving of different temples.

Those of Abu Simbel presented the most formidable challenge. Some ofthe proposals presented were imaginative; one was to leave the temples in situ but separate them from Lake Nasser

by means of a transparent dam filled with clear water.

Visitors would be able to view the temple from small chambers lowered from the surface of the lake.

The scheme chosen finally was more feasible and less costly.

It was tendered by a Stockholm company of consulting engineers and came to be known as the VBB Scheme.

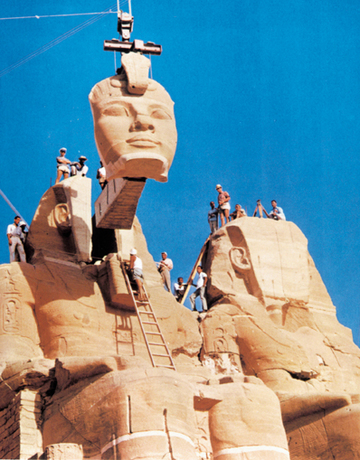

It entailed sawing the temple and its surrounding cliff into over a thousand pieces (some of which weighed up to fifteen tons) and transporting them to be reassembled at a new site sixty-four meters above their original positions.

The project involved five main stages.

First the construction of a coffer-dam. Second, studies to decide how the monument should be sectioned.

Then dismantling, storage, and final re-erection, The project to salvage the temples of Abu Simbel was an extraordinary task, since time was a vital factor, and also because nothing like it had ever been attempted before.

It was an archaeological rescue operation.

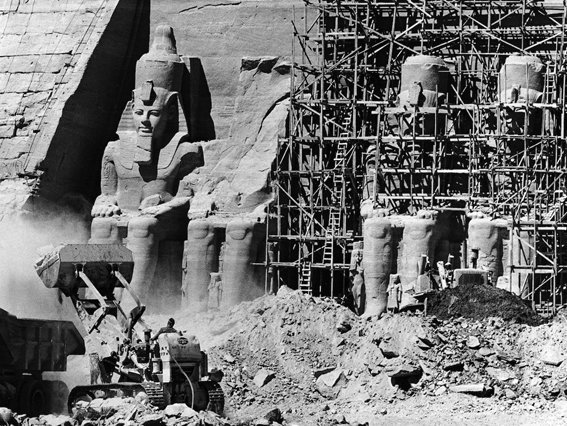

The drama of carving up the mountain began in the spring of 1962.

The fronts of the temples were reburied in sand, rather as originally discovered by Belzoni, to protect them from damage.

Then the tops of the cliffs were progressively dug away until the facade and its inner temple were reached.

At that point, cliff face, facade, and temples were carefully carved into blocks, each block num» bered, fitted with lifting bolts, and then carried away to an adjacent storage area.

Delicate features were riveted to larger blocks of concrete for stability.

While the sectioning and salvage was being.

done, the new site on top of the mountain was prepared.

Explosives could not be employed for fear of damaging the monuments, so compressed-air drills were used.

The bedrock was cored to en sure it could support the enormous weight that it was destined to bear forever-not only of the reconstructed temples but also of the great reinforced concrete domes that would protect the temples and support the new ‘hills’ that were built over them.

The dome of the great temple is twenty-five meters high and has a free span of some sixty meters. This single structure was designed to bear a load of about 100,000 tonnes and is itself a unique technological achievement. The project was finally completed in December 1968.

The temples had been reassembled in their new location, maintaining their original orientation. The temples were placed in small artificial hills (of forty meters and twenty-seven meters in height) rather than reconstructing the original sixty-five-meter cliff face.

The rock faces surrounding the temples, however, have been realistically reproduced. Viewed from the reverse (western) Side, the hills have been left deliberately artificial.

Unfortunately, the faces of Ramses II, once obscured for centuries by drifts of sand, are now slowly being eroded by sand particles.

It has beer: suggested that, being now raised above the plateau, the temple fronts are more exposed to windblown sand than previously.

1ater the cause, it illustrates the somewhat depressing fact that no matter how well monuments are restored, conserved. or salvaged and reconstructed, the efforts made are no more than temporary measures to delay an inevitable process of destruction, which ,accelerates from the moment they are released from their protective sand burial.