Ramses II History

Ramses II History (c. 1290-1224 B.c.) was the second son of Seti 1, the Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh whose temples on the Theban necropoiis and at Abydos are well known.

Ramses was born tkingship: ‘an inscription in his father’s mortuary temple at Abydos relates how he took the infant in his arms and showed him to the people as their king, telling them that he was destined to wear the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

At the age of twelve Ramses was appointed.

with Seti I and eventually became sole ruler when his father died.

In the twenty-first year ofhis reign, Egypéthad already over- extended its military power in westem Asia and the fluctuating frontier between Egypt and the Hittite armies in the north had exhausted both sides.

Finally a treaty was drawn up that became the nrst non-aggression pact history, After that we hear of no more wars, but there is indication that the pharaoh married a Hittite princess.

She became his third wife after Ast- nefert and his favorite and most beloved Nefertari, whose rock-hewn temple at Abu Simbel stands to the north of Ramses’ own.

These three legitimate wives, along with a host oflesser wives, produced a very large family. According to an inscription on the walls of Ramses’ temple at Wadi Sebua in Nubia, he had no fewer than 170 children, of whom 111 were male.

Forforty-six years after the treaty with the Hittites, Ramses lived at peace with his neighbors, and he became obsessed with the idea of founding new cities, building fortresses, and increas-ing the number of monolithic statues and obelisks bearing his name.

The last years of his life seem to have been spent peacefully indulging his passion for construction, building dikes, digging canals, and erecting mighty monuments through- out Egypt, especially at his capital Tanis in the northeastern Delta, and at Luxor.

In Nubia he constructed six temples between the First and Second Cataracts.

He sometimes usurped monuments built by his predecessors, or added extensions to them on such a scale that they dwarfed the original designs.

As a consequence, Ramses II History majestic monuments have survived the ravages of time better than any others.

He had an unusually long reign ofsixty-seven years and may have reached the ripe age of eighty. Due to the scanty strip ofvalley, many ofthe monuments in Nubia were hewn out of the rocky outcrops overlooking the river.

Some had freestanding statues leading from the clitfface to the river bank, and were erected at places where there is no apparent earlier building activity.

it is not clear why he chose some of the sites, and one can only assume that they were areas of sutticient importance to induce temple construction; in other words, to emphasize an Egyptian presence in the region.

Some of the temples were built by the viceroys of Kush, powerful officials who were second only to the king.

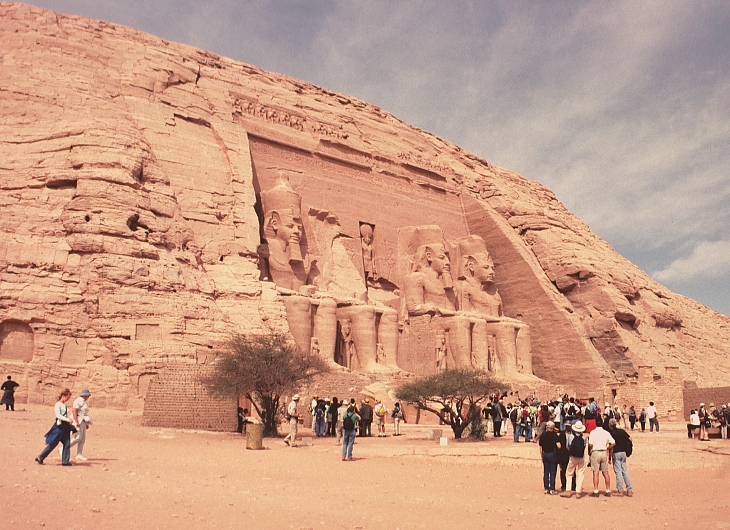

These viceroys inciuded Setau, who oversaw the construction of Ramses II History chapel (Beit al-Wali) and the largest and most impressive monuments ofali, those of Abu Simbel. Ramses chose a location 28() kilometers south of Aswan for the construction of these imposing monuments.

It was a site sacred to a deity associated with the westem hills, a goddess named Hathor of Abshek.

She was honored in the smaller temple ofNefertari, where several inscriptions mention that it was cut in the “holy mountain.”

The Great Temple of It is actually the cliff cut away in imitation of a temple frontage, crowned by a frieze of baboons.

It is thirty-two meters high, and the base is thirty-five meters wide.

The statues are approximately the same size as the broken granite colossus of Ramses II History in the Ramesseum on the Theban necropolis.

The pharaoh is seated with his hands on his knees.

The cartouches (the elliptical signs that denote kingshipl on his chest and upper arm bear his name.

On his forehead is sacred uraeus (cobra), the symbol of kingship, and he wears double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The task of fashioning these statues must have been tremendous.

The rugged mountain facing the river had first to be cut back while the four statues with their faces toward the rising run were left as outcrops of rock for later detailed carving, two to the left of the doorway and two to the right.

Side by side, Ramses II History (or perhaps with hi s double, his 6 sits in majesty, feet slightly apart. Ramses’ facial features, viey-.efi from ground level, appear somewhat distorted.

He is unduly wide across the cheekbones and his jaw seems too large.

However, when the temples were dismantled and it was possible to see the pharaoh’s head at close to be equally as handsome as those on his other statues.

The southern statue (a) is the best preserved.

The next tb) is shattered to the waist, with Ramses’ head lying at his fleet. The third statue (c) is nearly perfect, while the fourth id).

no of me four seated colossi of Ramses II History Ln the facade of his great temple at Abu Simbel. Photograph by greater part of the uraeus on the forehead, and oth arms and part of the torso are broken, Around and between the colossi are members of the royal feach side ofthe two colossi to the north are representa- Hapi, the Nile-god, twice represented binding together felcoral symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, the papyree and one otus.

Below is a row oi captives: Nubian prisoners to the south, Syrians to the north.

The left leg ofthe colossus flanking the doorway to the north ic) bears the well-known Greek inscription written in the reign of Psamtik II, the,Twenty-six Dynasty pharaoh, attesting to his passage southward “as far as the river permitted.” At the top of the facade, above the colossi and below the row of baboons, are two inscriptions.

The one to the south describes the king as “beloved of Amun-Re,” that to the north as “beloved of Re-Harakhte.” Above the doorway in the center of the facade, the hawk-headed Re-Harakhte has been carved sittingin a niche.

He is worshiped on either side by Ramses ll, who presents him oath tiny statuettes of Maat, the goddess of Truth and Justice.

The massiveness of this great rock-hewn temple is illus- trated by the size of they doorway, itself over seven meters high, which does not even reach to the level of the elbows of the colossi.

This doorway leads through a narrow passage into the central hall (1), which is eighteen meters long, sixteen meters wide, and eight meters high.

The ceiling is adorned with vultures (over the central aisle) and with stars and the names and titles of the king.

These titularies include the five elernents common to all pharaohs, each followed by a name particular to the individual king.

Here we have the Horus name of Ramses il, which identities him as the earthly of the falcon-god Horus; a nebty or “Two Ladies’ name, showing he is protected by the principal goddesses of the early dynasties Nekhbet the vulture-goddess of Upper Egypt and Wadjet the cobra-goddess of Lower Egptl; a ‘golden Horus titlef which reveals an aspect of Ramses il, in this case ‘ljowerful of Strength ;’ the prenornen, enclosed in a cartouche and preceded by the title ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt f and the nornen (also enclosed in a cartoachel, which is introduced hy epithet ‘son of the Sun-god L ne nave of the central hall is divided from the side aisles by two rows of statues of Ramses in Osiride form, with the crook and the flail across his chest.

He stands against a corresponding number of square pillars.

The statues on the north show the king wearing the double crown; on the south, he wears the

white crown of Upper Egypt.

The figures are well preserved and, despite the somewhat confined space in the chamben almost overpowering.

The faces of three of the statues to the north are in particularly good condition.

On the pillars at the back of the colossi are representations of the king before various gods, including Amun-Re, Harakhte, Ptah, Horus,Atum, Thoth, Min, Khnum and his two goddesses ofthe Aswan Cataract, Satis and Anukis, Hathor, Isis, and others.

The walls of the central chamber teem with beautifully painted reliefs.

Most depict religious ceremonies, or battle scenes in which Ramses, accompanied by his ka or spirit, clasps his enemies by the hair or smites them with a club.

He slays Nubians before Amun-Re and Libyans before Re-Harakhte,

The latter god rewards him with the curved sword of victory.

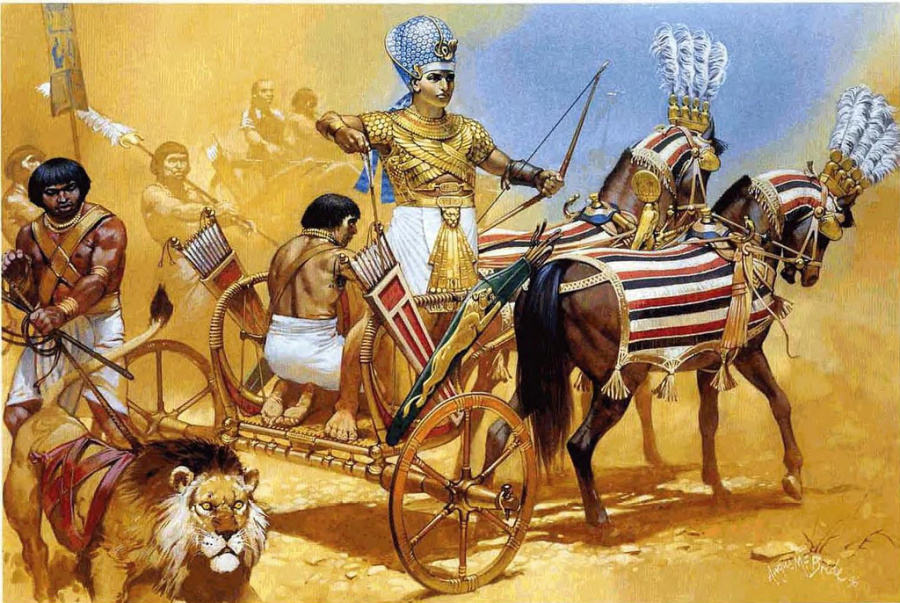

The northem wall of the hall is decorated with Ramses’ great battle scene.

This is one of the most extraordinary and detailed reliefs in the whole of Egypt.

It is eighteen meters long and eight metershigh and includes over 1,100 figures.

The huge scene represents not a single action but an entire military campaign.

The battle was fought at Kadesh, a city on the Orontes river in Syria, during the fifth year of Ramses’ reign. His foes were the Hittite King Kuwattalish and a coalition of neighboring chiefs. In the scene on the right, Ramses holds a council ofwar with his officers. In the register immediately below his seated figure, two spies are being interrogated. The text informs us that they were two men of the Shasu tribe from the land of’I‘chal. They claimed to have been sent by their chiefs to inform Ramses that They said the enemy were still some distance away.

This was far from true.

The two men had, in fact, been sent by the Hittite leaders armed with false information in order to ascertain the exact position ofthe Egyptian army.

The`Hittite army itselfwas arrayed for battle behind Kadesh. Fortunately Egyptian scouts arrested the spies and brought them back to camp, where they confessed.

Ramses II History subsequently put his army on alert and prepared to march on Kadesh.

The clash of armies is depicted in the upper register, where the river Orontes winds through the scene, almost surrounding the besieged city.

Ramses II History stands undaunted in his chariot.

He whips up his horses and dashes into the Hittite ranks, launching arrows and crushing many beneath his wheels.

Among the slain and the fallen some beg for mercy.

Of all the battle reliefs of ancient Egypt, this is the H1055 spectacular portrayal of all the pomp and circumstance of war. Ramses was later extolled by the court poet Pentauri Of* / No ofhcer was with me, no charioteer,

I found my heart stout my breast in joy,

. ’ D 1

évf I shot on my right-grasped OH my lem

5

I found the mass of chariots in whose midst I was

Scattering before my horses ….

Their hearts failed in their bodies through fear of me,

Their arms all slackened, they could not shoot. _V

They fell on their faces, one on the other.

Whoever fell down did not rise.

(Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature II, p.65)

So pleased was Ramses with the poem that henhad lt inscribed on the walls of many of his temples,

entrance pylon ofthe temple of Luxor andthe Ram€SS€\lm on theTheban necropolis. Nowhere, however, is the battle scene so graphically depicted as in Abu Simbel.

Some ofthe enemy peer down from the battlements to the scene below: the Egyptian army with its infantry and charioteers engage in hand-Ito-hand combat, the vanquished flee, prisoners are shown, the slain and wounded, and the enemy drowning in the river.

We see over-turned chariots, riderless horses, and farmers anxiouslying their cattle into the hills.

In another scene, the king, still in his chariot, inspects his officers after the battle as they count the severed hands of the enemy and bring in This scene is depicted on the extreme right of the wall

upper register.

On the lower half of the wall between the two doors are scenes of Egyptian camp life. The camp is square. and enclosed by a stockade of soldiers’ shields.

The royal tent is Shown find, at the center of the camp, Ramses’ pet lion is hem; CHl`€d fm’ by a keeper. Horses are fed in rows from a coninion manger.

Some paw the ground impatiently, others lie down or are harnessed.

One makes offwith an empty chariot and is pursued by 3 C0}1Ple of grooms. Joints of meat stand in the corner with a tripod

brazier. Soldiers eat from a common hnwl tim? “°“°l‘ ml their heels, One officer is shown having his wounded foot dressed by a doctor.

Another sits with his head resting on h1S hand. Hurrying toward him is a soldier, no doubt bringing neWS of the battle.

The rear wall (west) depicts Ramses leading captive Hittites toward Re-Harakhte and himself (depicted as a god) on the right.

On the left the king leads rows of captive Nubians to Amun-Re, Ramses as a deity, and the goddess Mut.

The doorway to the rear leads to a second hall (2), which is supported by four square pillars.

The walls are decorated with reliefs of offerings to the various gods.

Next is an ante-chamber (3) leading to the inner sanctuary (4).

The great temple of’ Ramses II History at Abu Simbel is so orientedthat twice a year the rising sun shines straight into the sanctuary to illuminate the statues of the gods to whom the temple is dedicated: Amun-Re of Thebes, Re-Harakhteof Heliopolis, Ptah of Memphis, and the deified Ramses II himself. Because of the pressure of’ visitors, entrance is restricted on these occasions. Recently, closed-circuit television has been used to relay the event to viewers on the terrace.

The Temple of Nefertari This temple, the smaller.

The names ofthe royal couple are linked in their shared dedication to the cow-goddess Hathor, who was associated with motherhood and later became a popular protectress of women.

The front of the temple was a daring architectural innovation.

It is a sloping facade with frames for six recesses, three on each side of the central doorway. Within each frame is a colossal and beautifully-carved standing figure, erect and lifelike. Four are ofthe king and two ofthe queen.

They appear to be striding straight out ofthe mountain. Ramses wears an elaborate crown of plumes and horns, while the graceful Iflefertari has a headpiece The facade of the temple of Nefertari at Abu. Simbel. Photograph by Carolyn Brown.

A ” f comprising phirhes and the lsi_1?i1isk. Small figures of their children stand at their sides, Qiellrincesses beside Nefergg and the princes beside Ramses.

They are three meters in hgght, and yet their heads reach only to the knees of their royal parents.

The temple contains ball,jra_u_s1&;se, chamber,The central hall (1) has six pillars crowned with Hathor heads and sistra, the musical instruments associated re representations of the royal couple and various deities.

Un the side walls, Ramses and Nefertari smite a Libyan in the presence of Re-Harakhte (a),

and a Nubian in the presence oi`Amun-Re (b). At c, RamS€S m8l<€S af* offering to Ptah and a ram-headed deity, Harshef, while Nefertari offers to Hathor. The scene atd shows Ramses standing before Hathor, being blessed by Horus and Seth of Nubia. Nefertari stands before Anukis, the daughter of the triad of Elephantine.

The rear walls show Nefertari and Hathor on the right, and Nefertari and Mut, the consort of Amun, on the left.

The transverse chamber (2) is decorated with reliefs and adjoined by two unfinished chambers. The sanctuary (3) has a recess to the rear.

The roof is supported by columnar representations of sistra.

On the rear wall is a figure of the divine cow emerging from a rock. It is a symbol ofthe world inaccessible to mortals, the afterlife. The milk of the goddess regenerates the souls of the dead.

It is an allusive form of materianity in the world The architectural magnificence of these two temples gives unique importance to Abu Simbel and Ramses II History.

The site was a staging point for river traffic between Egypt and Nubia and the immense

scale and elaboration ofthe monuments suggests that political objectives played an important part in their con struction.

Apart from the practical purpose of transshi ment of roducts, the main temple may have served as a strongroom. Per aps the side chambers, hewn into the depths of the rock, were store-

rooms where gold and copper mined from Nubia, or alternatively extracted from the Nubians as tribute, may have been stored.

Onward transportation to Egypt could then be carried out when conditions in the north were considered stable.

Whether or not the temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel served as a repository for treasure, it stressed the strength of the Egyptian presence in Nubia, and served a‘religious function: it demonstrated the power ofrebirth. Ramses II’s divine power was annually renewed by the sun.

The proximity of the temple of his divine spouse ensured that she would be forever by his side.