Qasr Ibrim

Riding above the waters of Lake Nasser, about fifteen kilometers north of Abu Simbel, is the island of Qasr Ibrim, all that remains of an important frontier post in Roman times, when it was still part of the mainland.

Although accessible to visitors only by special arrangement, it is included here because it is the only site in Egyptian hlubia where excavations are still being carried out.

Moreover, Qasr Ibrim may soon be included on the cruise of Lake Nasser from Aswan to Abu Simbel.

Of the three massive rocks that once rose above the river, only a part of the middle peak is visible today.

The site, crowned by a fortress, commanded aview ofthe Nile Valley and desert for miles around. During the Roman occupation of Egypt between 30 B.c. and A.D. 395, Qasr Ibrim was regarded, as were Elephantine and Philae during earlier periods, as the official border between Egypt and Nubia.

The fortification of Qasr Ibrim by the Roman general Petronius is well documented. His task (see p.24) was to contain the Blemmys and the Nobodai tribes of the Eastern and Western Deserts.

To this end he established a stronghold. It is thought, however, that the site may have been a center of activity much earlier.

The discovery of a mud-brick temple built by Taharqa, whose predecessors founded the Kushite Dynasty around 720 B.c., attests to this. But because there was no resident community to maintain the temple, which was situated near the south gate, it fell to ruin soon after construction. Parts of it were later reused in the foundations of a nearby temple built in Meroitic times.

It is difficult to date the Meroitic (Kushite) temple.

Some scholars think it was constructed’ after the Roman occupation. If that was the case, Qasr Ibrim may have been the last Meroitic outpost and perhaps of greater religious than military import to them.

When the Blemmys and Nobodai later occupied the site, it was a place of pilgrimage, perhaps the very site to which the sacred statue of isis was borne from Philae .

The function of Qasr Ibrim in early Christian times seems to have been of little consequence. Pilgrims continued to congregate in a large open plaza.

which was clearly designed to accommodate large numbers of people.

Despite evidence of added fortitication, however, life seems to have continued much the same as it always did.

The inhabitants of Qasr Ibrim may have converted to Christianity at the same timeas those on Philae, although the official conversion of the Nobodai came only later.

This happened at the beginning of the sixth century, when the ruined Taharqa temple was converted into a church.

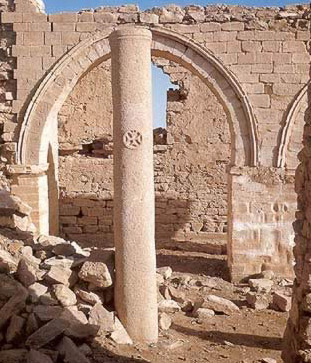

A great cathedral was later built on the site.

Opposite: The salvage operation at Abu Simbel: rebuilding the great temple of Ramses II. Photograph from The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples, A.R.E. Ministry of Culture, 1971.

No noticeable change took place at Qasr Ibrimoeven after the Arab conquest. Only in 1173, when Nubia was invaded by Turan Shah, the elder brother of Salah al-Din, was Qasr Ibrim finally besieged.

The Meroites were defeated, the town de- stroyed, and the wh ole population imprisoned. The cross on the dome of the church was burned and the bishop captured. Seven hundred pigs, considered unclean, were killed on the spot.

A Muslim garrison was set up at Qasr Ibrim in the sixteenth century. According to local tradition-yet to be substantiated by archaeological evidence–it was manned by Bosnians.

They were subsequently forgotten at the fortress and went on living there, expanding their settlement, until the nineteenth century.

A part of the cathedral was converted into a mosque, and a dense cluster of new buildings arose on the ruins of the old. In its phases as an artillery base and a religious center, the island’s ruins range from temple to cathedral.

Among the most important discoveries so far made there are ancient documents.

Written in a host of languages, including old Nubian (yet to be deciphered), Arabic, Coptic, and Greek, are private and official letters, legal documents, and petitions, dating from between the end of the eighth and the fifteenth centuries.

Archaeological excavation of the ruined town and fortress is being carried out by the Egypt Exploration Society under the directorship of Mark Horton.

Restoration of the cathedral is one of the long-term projects envisioned.