Medieval Egypt

The Arab Conquest, 639-41

Perhaps Medieval Egypt the most important event to occur in Egypt since the unification of the Two Lands by King Menes was the Arab conquest of Egypt.

The conquest of the country by the armies of Islam under the command of the Muslim hero, Amr ibn al As, transformed Egypt from a predominantly Christian country to a Muslim country in which the Arabic language and culture were adopted even by those who clung to their Christian or Jewish faiths.

The conquest of Egypt was part of the Arab/Islamic expansion that began when the Prophet Muhammad died and Arab tribes began to move out of the Arabian Peninsula into Iraq and Syria. Amr ibn al As, who led the Arab army into Egypt, was made a military commander by the Prophet himself.

Amr crossed into Egypt on December 12, 639, at Al Arish with an army of about 4,000 men on horseback, armed with lances, swords, and bows.

The army’s objective was the fortress of Babylon (Bab al Yun) opposite the island of Rawdah in the Nile at the apex of the Delta.

The fortress was the key to the conquest of Egypt because an advance up the Delta to Alexandria could not be risked until the fortress was taken.

In June 640, reinforcements for the Arab army arrived, increasing Amr’s forces to between 8,000 and 12,000 men. In July the Arab and Byzantine armies met on the plains of Heliopolis. Although the Byzantine army was routed, the results were inconclusive because the Byzantine troops fled to Babylon. Finally, after a six-month siege, the fortress fell to the Arabs on April 9, 641.

The Arab army then marched to Alexandria, which was not prepared to resist despite its well fortified condition. Consequently, the governor of Alexandria agreed to surrender, and a treaty was signed in November 641.

The following year of Medieval Egypt, the Byzantines broke the treaty and attempted unsuccessfully to retake the city.

Muslim conquerors habitually gave the people they defeated three alternatives: converting to Islam, retaining their religion with freedom of worship in return for the payment of the poll tax, or war. In surrendering to the Arab armies, the Byzantines agreed to the second option.

The Arab conquerors treated the Egyptian Copts well. Medieval Egypt

During the battle for Egypt, the Copts had either remained neutral or had actively supported the Arabs.

After the surrender, the Coptic patriarch was reinstated, exiled bishops were called home, and churches that had been forcibly turned over to the Byzantines were returned to the Copts.

Amr allowed Copts who held office to retain their positions and appointed Copts to other offices.

Amr moved the capital south to a new city called Al Fustat (present-day Old Cairo).

The mosque he built there bears his name and still stands, although it has been much rebuilt.

For two centuries after the conquest, Egypt was a province ruled by a line of governors appointed by the caliphs in the east.

Egypt provided abundant grain and tax revenue.

In time most of the people accepted the Muslim faith, and the Arabic language became the language of government, culture, and commerce. The Arabization of the country was aided by the continued settlement of Arab tribes in Egypt.

From the time of the conquest onward, Egypt’s history was intertwined with the history of the Arab world.

Thus, in the eighth century, Egypt felt the effects of the Arab civil war that resulted in the defeat of the Umayyad Dynasty, the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate, and the transfer of the capital of the empire from Damascus to Baghdad.

For Egypt, the transfer of the capital farther east meant a weakening of control by the central government.

When the Abbasid Caliphate began to decline in the ninth century, local autonomous dynasties arose to control the political, economic, social, and cultural life of the country

Medieval Egypt The Tulinids, Ikhshidids, Fatimids, and Ayyubids, 868- 1260

A new era began in Egypt with the arrival in Al Fustat in 868 of Ahmad ibn Tulun as governor on behalf of his stepfather, Bayakbah, a chamberlain in Baghdad to whom Caliph Al Mutazz had granted Egypt as a fief. Ahmad ibn Tulun inaugurated the autonomy of Egypt and, with the succession of his son, Khumarawayh, to power, established the principle of locally based hereditary rule.

Autonomy greatly benefited Egypt because the local dynasty halted or reduced the drain of revenue from the country to Baghdad.

The Tulinid state ended in 905 when imperial troops entered Al Fustat.

For the next thirty years, Egypt was again under the direct control of the central government in Baghdad.

The next autonomous dynasty in Egypt, the Ikhshidid, was founded by Muhammad ibn Tughj, who arrived as governor in 935.

The dynasty’s name comes from the title of Ikhshid given to Tughj by the caliph.

This dynasty ruled Egypt until the Fatimid conquest of 969.

The Tulinids and the Ikhshidids brought Egypt peace and prosperity by pursuing wise agrarian policies that increased yields, by eliminating tax abuses, and by reforming the administration. Neither the Tulinids nor the Ikhshidids sought to withdraw Egypt from the Islamic empire headed by the caliph in Baghdad.

Ahmad ibn Tulun and his successors were orthodox Sunni Muslims, loyal to the principle of Islamic unity.

Their purpose was to carve out an autonomous and hereditary principality under loose caliphal authority.

The Fatimids, the next dynasty to rule Egypt, unlike the Tulinids and the Ikhshidids, wanted independence, not autonomy, from Baghdad.

In addition, as heads of a great religious movement, the Ismaili Shia Islam (see Glossary), they also challenged the Sunni Abbasids for the caliphate itself.

The name of the dynasty is derived from Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad and the wife of Ali, the fourth caliph and the founder of Shia Islam.

The leader of the movement, who first established the dynasty in Tunisia in 906, claimed descent from Fatima.

Under the Fatimids, Egypt became the center of a vast empire, which at its peak comprised North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Syria, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Yemen, and the Hijaz in Arabia, including the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

Control of the holy cities conferred enormous prestige on a Muslim sovereign and the power to use the yearly pilgrimage to Mecca to his advantage.

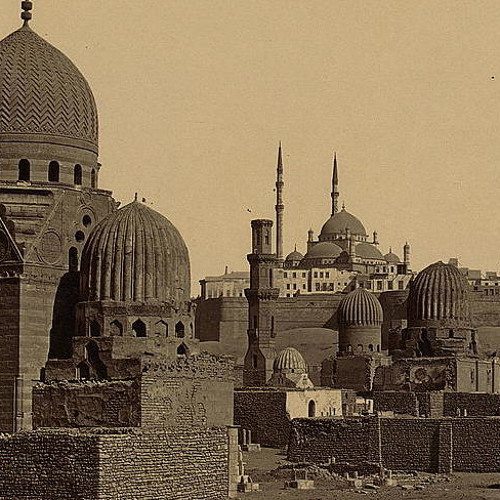

Cairo was the seat of the Shia caliph, who was the head of a religion as well as the sovereign of an empire.

The Fatimids established Al Azhar in Cairo as an intellectual center where scholars and teachers elaborated the doctrines of the Ismaili Shia faith.

The first century of Fatimid rule represents a high point for medieval Egypt.

The administration was reorganized and expanded.

It functioned with admirable efficiency: tax farming was abolished, and strict probity and regularity in the assessment and collection of taxes was enforced.

The revenues of Egypt were high and were then augmented by the tribute of subject provinces.

This period was also an age of great commercial expansion and industrial production.

The Fatimids fostered both agriculture and industry and developed an important export trade.

Realizing the importance of trade both for the prosperity of Egypt and for the extension of Fatimid influence, the Fatimids developed a wide network of commercial relations, notably with Europe and India, two areas with which Egypt had previously had almost no contact.

Egyptian ships sailed to Sicily and Spain.

Egyptian fleets controlled the eastern Mediterranean, and the Fatimids established close relations with the Italian city states, particularly Amalfi and Pisa.

The two great harbors of Alexandria in Egypt and Tripoli in present-day Lebanon became centers of world trade. In the east, the Fatimids gradually extended their sovereignty over the ports and outlets of the Red Sea for trade with India and Southeast Asia and tried to win influence on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

In lands far beyond the reach of Fatimid arms, the Ismaili missionary and the Egyptian merchant went side-by-side.

In the end, however, the Fatimid bid for world power failed. A weakened and shrunken empire was unable to resist the crusaders, who in July 1099 captured Jerusalem from the Fatimid garrison after a siege of five weeks.

The crusaders Medieval Egypt

were driven from Jerusalem and most of Palestine by the great Kurdish general Salah ad Din ibn Ayyub, known in the West as Saladin.

Saladin came to Egypt in 1168 in the entourage of his uncle, the Kurdish general Shirkuh, who became the wazir, or senior minister, of the last Fatimid caliph.

After the death of his uncle, Saladin became the master of Egypt.

The dynasty he founded in Egypt, called the Ayyubid, ruled until 1260.

Saladin abolished the Fatimid caliphate, which by this time was dead as a religious force, and returned Egypt to Sunni orthodoxy.

He restored and tightened the bonds that tied Egypt to eastern Islam and reincorporated Egypt into the Sunni fold represented by the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.

At the same time, Egypt was opened to the new social changes and intellectual movements that had been emerging in the East. Saladin introduced into Egypt the madrasah, a mosque-college, which was the intellectual heart of the Sunni religious revival.

Even Al Azhar, founded by the Fatimids, became in time the center of Islamic orthodoxy.

In Medieval Egypt 1193 Saladin died peacefully in Damascus.

After his death, his dominions split up into a loose dynastic empire controlled by members of his family, the Ayyubids. Within this empire, the Ayyubid sultans of Egypt were paramount because their control of a rich, well-defined territory gave them a secure basis of power.

Economically, the Ayyubid period was one of growth and prosperity. Italian, French, and Catalan merchants operated in ports under Ayyubid control. Egyptian products, including alum, for which there was a great demand, were exported to Europe.

Egypt also profited from the transit trade from the East. Like the Fatimids before him, Saladin brought Yemen under his control, thus securing both ends of the Red Sea and an important commercial and strategic advantage.

Culturally, too, the Ayyubid period was one of great activity. Egypt became a center of Arab scholarship and literature and, along with Syria, acquired a cultural primacy that it has retained through the modern period.

The prosperity of the cities, the patronage of the Ayyubid princes, and the Sunni revival made the Ayyubid period a cultural high point in Egyptian and Arab history.

Medieval Egypt The Mamluks, 1250-1517

To understand the history of Egypt during the later Middle Ages, it is necessary to consider two major events in the eastern Arab World: the migration of Turkish tribes during the Abbasid Caliphate and their eventual domination of it, and the Mongol invasion.

Turkish tribes began moving west from the Eurasian steppes in the sixth century. As the Abbasid Empire weakened, Turkish tribes began to cross the frontier in search of pasturage.

The Turks converted to Islam within a few decades after entering the Middle East.

The Turks also entered the Middle East as mamluks (slaves) employed in the armies of Arab rulers. Mamluks, although slaves, were usually paid, sometimes handsomely, for their services.

Indeed, a mamluk’s service as a soldier and member of an elite unit or as an imperial guard was an enviable first step in a career that opened to him the possibility of occupying the highest offices in the state. Mamluk training was not restricted to military matters and often included languages and literary and administrative skills to enable the mamluks to occupy administrative posts.

In the late tenth century, a new wave of Turks entered the empire as free warriors and conquerors. One group occupied Baghdad, took control of the central government, and reduced the Abbasid caliphs to puppets. The other moved west into Anatolia, which it conquered from a weakened Byzantine Empire.

The Medieval Egypt Mamluks had already established themselves in Egypt and were able to establish their own empire because the Mongols destroyed the Abbasid caliphate. In 1258 the Mongol invaders put to death the last Abbasid caliph in Baghdad.

The following year, a Mongol army of as many as 120,000 men commanded by Hulagu Khan crossed the Euphrates and entered Syria.

Meanwhile, in Egypt the last Ayyubid sultan had died in 1250, and political control of the state had passed to the Mamluk guards whose generals seized the sultanate.

In 1258, soon after the news of the Mongol entry into Syria had reached Egypt, the Turkish Mamluk Qutuz declared himself sultan and organized the successful military resistance to the Mongol advance.

The decisive battle was fought in 1260 at Ayn Jalut in Palestine, where Qutuz’s forces defeated the Mongol army.

An important role in the fighting was played by Baybars I, who shortly afterwards assassinated Qutuz and was chosen sultan. Baybars I (1260-77) was the real founder of the Mamluk Empire. He came from the elite corps of Turkish Mamluks, the Bahriyyah, socalled because they were garrisoned on the island of Rawdah on the Nile River.

Baybars I established his rule firmly in Syria, forcing the Mongols back to their Iraqi territories.

At the end of the fourteenth century, power passed from the original Turkish elite, the Bahriyyah Mamluks, to Circassians, whom the Turkish Mamluk sultans had in their turn recruited as slave soldiers.

Between 1260 and 1517, Mamluk sultans of TurcoCircassian origin ruled an empire that stretched from Egypt to Syria and included the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. As “shadow caliphs,” the Mamluk sultans organized the yearly pilgrimages to Mecca.

Because of Mamluk power, the western Islamic world was shielded from the threat of the Mongols.

The great cities, especially Cairo, the Mamluk capital, grew in prestige. By the fourteenth century, Cairo had become the preeminent religious center of the Muslim world.

Medieval Egypt EGYPT UNDER THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

In 1517 the Ottoman sultan Selim I (1512-20), known as Selim the Grim, conquered Egypt, defeating the Mamluk forces at Ar Raydaniyah, immediately outside Cairo.

The origins of the Ottoman Empire go back to the Turkish-speaking tribes who crossed the frontier into Arab lands beginning in the tenth century.

These Turkish tribes established themselves in Baghdad and Anatolia, but they were destroyed by the Mongols in the thirteenth century.

In the wake of the Mongol invasion, petty Turkish dynasties called amirates were formed in Anatolia.

The leader of one of those dynasties was Osman (1280-1324), the founder of the Ottoman Empire. In the thirteenth century, his amirate was one of many; by the sixteenth century, the amirate had become an empire, one of the largest and longest lived in world history.

By the fourteenth century, the Ottomans already had a substantial empire in Eastern Europe. In 1453 they conquered Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, which became the Ottoman capital and was renamed Istanbul. Between 1512 and 1520, the Ottomans added the Arab provinces, including Egypt, to their empire.

In Egypt the victorious Selim I left behind one of his most trusted collaborators, Khair Bey, as the ruler of Egypt. Khair Bey ruled as the sultan’s vassal, not as a provincial governor.

He kept his court in the citadel, the ancient residence of the rulers of Egypt.

Although Selim I did away with the Mamluk sultanate, neither he nor his successors succeeded in extinguishing Mamluk power and influence in Egypt.

Medieval Egypt

Only in the first century of Ottoman rule was the governor of Egypt able to perform his tasks without the interference of the Mamluk beys (bey was the highest rank among the Mamluks). During the latter decades of the sixteenth century and the early seventeenth century, a series of revolts by various elements of the garrison troops occurred. During these years, there was also a revival within the Mamluk military structure. By the middle of the seventeenth century, political supremacy had passed to the beys.

As the historian Daniel Crecelius has written, from that point on the history of Ottoman Egypt can be explained as the struggle between the Ottomans and the Mamluks for control of the administration and, hence, the revenues of Egypt, and the competition among rival Mamluk houses for control of the beylicate.

This struggle affected Egyptian history until the late eighteenth century when one Mamluk bey gained an unprecedented control over the military and political structures and ousted the Ottoman governor.