The High Dam

High Dam To a Greek-Egyptian agifonomist, Andrian Dannios, must go credit for the idea of building a dam at Aswan so large that it could provide for long-term storage of water as well as protect against high and low floods.

His concept was not, however, to take root until after the 1952 Revolution, when Gamal Abd al-

Nasser saw the construction of a High Dam as essential to the country’s economic development. His decision to build the dam arose from a number of considerations, not the least of which was the fact that Egypt’s population was twenty-eight million people by 1960.

Estimates at that time indicated that within twenty years it would soar to forty million.

The country could not, therefore, be expected to live long within the limits of its current food resources.

Agricultural output was already reaching its maximum potential.

It was considered urgent to increase the amount of arable land and the High Dam (al-Sadd al-Aali) was_ seen as the answer.

stabilize the river and provide adequate, but not excessive, irrigation all year round.

enable Egypt’s cultivable land to be dramatically increased, and at the same time it would provide hydroelectric power sufficient to bring electricity to villages and industry throughout the country, It was clear from the beginning that there would be many adverse affects from such a dam, not the least of which was that the whole of Egyptian Nubia, its contemporary settlements,

towns, and cemeteries, as well as important archaeological sites, would be lost beneath the reservoir.

Such serious problems could not wait for ideal solutions, Steps were immediately taken to relocate the entire population of Nubia.

Eventually some fifty thousand people from the southern part of Nubia found a new home in Qasr al-Girba in Sudan, and an equal number from Lower (Egyptian) Nubia in the north were relocated to Kom Ombo, north ofAswan.

As for the historical and archaeological heritage of Nubia, Egypt and Sudan launched an international appeal through UNESCO and during the period that the dam was being built between 1960 and 1971, twenty-three temples and shrines were saved.

One complete temple, built by Queen Hatshepsut at Semna, was dismantled and transported in fifty nine cases aboard twenty-eight trucks to Khartoum, where it was eventually reconstructed in the National Museum.

The temple of Amada was lifted as a unit, put on rails, and dragged up a hill to safety by a French government team.

Other monuments were shipped across the sea to museums around the world: the Greco-Roman temple of Debod, for example, now stands on a cliff in Madrid; another temple of the same period has been reconstructed in a courtyard of the Museum in Leiden; the Temple of Dendur is the main feature of a special hall in the Metropolitan Museum in New York; and a small Eighteenth

Dynasty temple started by Thutmose III can today be found in the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

Two of the greatest salvage operations were those of the monuments of Philae (see Chapter 3) and the rock-hewn temples of Ramses II at Abu Simbel (see Chapter 6).

Three other monuments from Nubia have been saved and reconstructed near the High Dam, in an area now known as New Kalabsha.

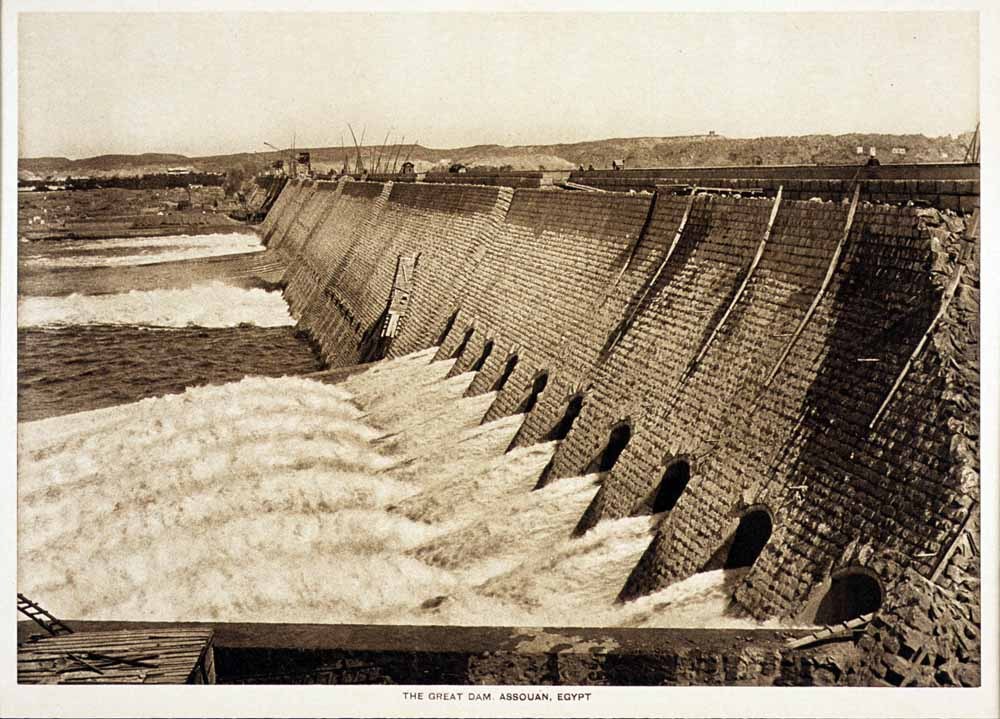

They are the temple of Kalabsha itself, the memorial chapel of Ramses II (known a , and the kiosk of Kertassi The High Dam was constructed between 1960 and 197 1, six and a half kilometers south of Aswan.

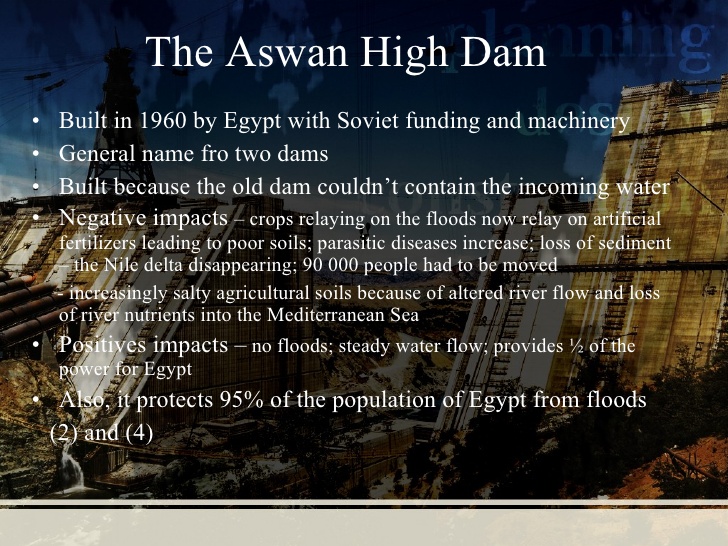

It was largely financed and supervised by the Soviet Union, after the withdrawal of US and British financial aid for the project, which had been estimated at $1,500 million.

It was a complex construction on a monumental scale.

Seventeen million cubic meters of rock were excavated, and 42,700,000 cubic meters of material were used in the con struction of a virtual mountain of earth and rock over acement and clay core. The crest of the dam runs for 520 meters across the river.

Two wings extend on both banks so that the total length of the dam structure is 3,830 meters.

The dam is 114 meters high at its highest point, and the width at the base is 980 meters. The diversion canal, through which the water of the Nile now flows through six tunnels dug in the rocks beneath the right wing of the dam, is 1,950 meters long.

North of the tunnels lie the dam’s power stations.

The labor of thirty thousand men working in shifts day and night for ten years under the supervision of two thousand

technicians was needed to block the flow ofthe Nile.

The water then swelled back upon itself and formed a reservoir, LakeNasser, over five hundred kilometers in length (350 in Egyptian Nubia and 150 in Sudan)..

Its width ranges between eight and fifteen kilometers, and it has a storage capacity of 162 billion inenlgn Uam we cubic meters.

It is the largest artificial lake in the world.

The High Dam was heralded as a miracle; a dam to dwarf all dams. It was the final answer to hamessing the mighty Nile for the benefit of human development.

When he officially opened the High Dam, Egypt’s President Abd al-Nasser detonated a charge that broke the last barrier and allowed the Nile to rush into the diversion canal.

The dramatic impact of this moment in history was underplayed by the media; it was lost by journalists who, enraptured by impres- sive statistics, declared that this new artificial mountain was

seventeen times as big as the great pyramid of Khufii at Giza.

What they did not mention was the fact that on that memorable day Egypt’s vital waterway from Aswan to the Mediterranean Sea became no more than a channel, under human control.

Nowhere does technological advancement occur without some disadvantages.

Egypt is no exception.

Drawbacks must, however, be weighed against the benefits of economic development, and environmental change against achievements: as a result of the High Dam, drought and flooding have become dangers of the past.

Long-term water storage in Lake Nasser has already saved Egypt from serious water shortages (specifically during nine consecutive years of drought in Africa between 1979 and 1988).

It has also averted the danger of two serious floods, the most recent in 1975.

In addition, the increased water afforded by the dam has transformed 2.5 million acres of farmland from basin irrigation to the more profitable perennial irrigation, and there has been a dramatic increase in the amount of arable land (the goal set for the year 2000 is an extra 1.56 million acres). The hydroelectric power generated by the dam has a theoretical total gross output of eight billion kilowatt-hours per year, and large-scale industrial development has been supplied. `

Because the High Dam, unlike the earlier Aswan Dam, effectively stopped the Nile south of Aswan, silt rich in nutritive elements is no longer brought down by the river, affecting agriculture; this silt was also a basic component in making bricks.

Both problems were ‘seen as no more than temporary set backs.

Artificial fertilizer, it was argued, could replenish the soil, and a brick factory could be established immediately south of the dam on Lake Nasser, where the silt was presumed to be deposited.

Altematively, studies could be carried out on the possible use of shale for brick manufacture. Among other issues subsequently identified and discussed at length are the extent of water loss through seepage and evaporation, the consequences of the sedimentation in Lake Nasser (the silt now accumulates two hundred kilometers south of the anticipated area of deposit), and the effects of the higher water table and increased salinity of the soil on Egypt’s agricultural land.

Increased water discharge for the generation of`hydroelectric power has also resulted in a higher velocity of river flow, and consequently river-bed erosion, which could endanger the foundations of Nile bank historical monuments.

This was not foreseen.

Neither was the extent ofthe erosion ofthe Mediterranean coast, denied its annual rebuilding by the silt deposit.

The virtual disappearance of sardines in the Mediterranean around the Nile Delta was also not envisioned; this again was the effect of the absence of deposition of silt (a food source) at the mouths ofthe Nile.

The flow of water in the lower Nile and in main irrigation canals is being restricted by an increase in the growth of water hyacinths, the result of a change in the chemical makeup of the river.

The dramatic loss of some of the most fertile agricultural land in Egypt through urban development was also not anticipated: the stabilization of the river banks and the absence of the annual flood allow permanent dwellings to be built on the river bank for the first time in history.

Steps have been taken to minimize these adverse ecological changes.

The rate of coastal erosion on the Mediterranean, for example, is being monitored, and vulnerable areas are being reinforced with vast concrete blocks.

The effects of the higher water-table and increased salinity of the soil are being tackled by constructing a major drainage scheme throughout the Delta; this was unnecessary when the waters subsided naturally at the end ofthe annual flood.

The loss of fish off the mouths ofthe Delta is partly balanced by the development of a fishing industry on Lake Nasser.

The National Academy of Scientific Research in Egypt has been carrying out a joint project with the University of Michigan since 1974 to study the side effects of the dam.

Also, the Research Institute of the High Dam’s Side Effects (established in 1975 as part of the Water Research Center at the Ministry of Irrigation) is studying climatic conditions due to increased humidity, and the rate of water seepage appears to be decreasing with the passage of time.

The High Dam Monument

An elegant monument, symbol of friendship between Egypt and the Soviet Union, was built to mark the completion of the dam.

Its stylized shape represents a lotus blossom rising from an artificial pond, symbolizing the primordial ocean from which life began. ’ Within the stem of the lotus is a visitor’s pavilion, its concrete walls (the petals ofthe lotus) decorated in mosaic with themes that illustrate the benefits of the dam.

It is a legend of progress and hope.

To the west, facing the entrance, the first ‘petal’ shows the palms of two hands outlined in muted color. This is a symbol of cooperation between the two countries.

Above them, a fountain is depicted with the sprays of water flowing towards a verse of the Quran. Moving anti-clockwise to the second petal, there is a scene showing plants, reflecting the anticipated increase in agricultural land resulting from the stored water.

This is followed, on the third petal, by a scene that shows the flow of water into a hydroelectric plant and toward an industrial area.

The scenes include an Egyptian family, and illustrate sufficiency and progress.

The fourth and fifth petals relate a legend of hope for the Nubian people, dispossessed of their homeland and resettled’ in Kom Ombo: the sun emerges from the horizon; it casts light on the rising generation; there are books and crafts, representing learning and Nubian identity.