Egypt Prehistory

Egypt Prehistory As hard as may be to believe, there was an Egypt before the Pharaohs, Over a century ago, Charles Darwin, without any real evidence to back up his theory, set forth the statement that Africa might have been the cradle of the human race.

Today, we still have no conclusive proof, but many signs point to one of the first civilizations created by human-like beings might have been in the Nile Valley around 700,000 years ago, if not earlier.

Possible evidence to push the date back much earlier was found at Olduvai.

The Olduvai Gorge site in Tanzania is the oldest archaeological site in the world.

Discovered by Dr. Mary D. Leakey and her husband, Louis Leakey, it contains the remains of large hominids (humanlike creatures) almost two million years old, which they labeled as Zinjanthropus boisei.

But even more important than the remains themselves was the large amount of animal bones and crude stone tools found with them, evidence that these were intelligent beings.

The existence of these stone tools prompted archaeologists to label them the “Olduwan Industry.”

Remains of boisei and similar hominids,Egypt Prehistory

as well as the shelters they built and tools they used have been found in many places in Africa, from Lake Rudolph in eastern Africa, to South Africa, to the Afar and Omo river valleys in Ethiopia.

Unfortunately, to date, no remains of boisei or even of Australopithecus africanus and Homo habilis (two species of advanced hominids believed to be our ancestors) have been found in the Lower Nile Valley, but if human-like creatures were already roaming over Africa nearly two million years ago, it seems very likely they could have migrated to the Nile Valley.

Many archaeologists now believe,Egypt Prehistory

based on what has already been found at Olduvai and similar sites, that it is only a matter of time before remains of early hominids are found in Egypt.

There is a strong case for this, but until the discovery of australopithecine remains there, the evidence is still only circumstantial.

For nomadic tribes of hunter-gatherers, as some anthropologists believe our ancestors were, the fertile Nile Valley, with its readily available water, game, and arable land, must have looked inviting indeed. Additionally, this period is believed to have been much more temperate and rainy than the Nile Valley of today, and so one must imagine this area to be filled with wide expanses of grasslands, teeming with life, similar to the savannas of southern and eastern Africa.

These savannas may even have extended well into what is today the Sahara Desert, and oases such as the Karga Oasis and the Dungul Oasis are all that is left of these vast ranges of vegetation.

The Nile-Egypt Prehistory

may even have served as a migration route for early civilizations to make their way up through Africa and into Europe, beginning the spreading of the human race throughout the world.

At the very least, we can say early humans were in Egypt 700,000 years ago for certain. To date, the oldest tools found in the lower Nile Valley have been found in and near the cliffs of Abu Simbel, just across the river from where, millennia later, the descendants of these people would build the temple of Rameses II.

Geological evidence

indicates they are around 700,000 years old, giving a fairly good estimate as to when a Stone Age people was living in the area. “Slightly” later, dating to approximately 500,000 years ago, are various finds of stone tools, including the stone axes that the Lower Paleolithic is noted for. Gertrude Caton-Thompson and Elinor Gardner report industry in the Achulean Period (c. 250,000 – 90,000 BC) of the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. Paleolithic sites are most often found near dried-up springs or lakes, or in areas where materials to make stone tools are plentiful.

One of the most important finds from the Achulean Period is known as Arkin 8,

discovered by Polish archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski near the the Nile Valley town of Wadi Halfa.

Arkin 8, unlike many Paleolithic sites in Egypt, was not only remarkably well-preserved, but astonishingly rich.

Arkin 8 boasts the earliest known house-like structures in Egypt and the Sudan, some of the oldest buildings in the world. The structures are oval depressions around 30 cm deep and 1.8 x 1.2 meters across, many lined with flat sandstone slabs.

Most likely these are what are known as “tent rings,” in which a dome-like shelter of skins or brush was held down by heavy rocks lain in a circle.

This type of dwelling provides a permanent place to live, but if necessary, can be taken down easily and moved.

They are the dwelling that seems to be most favored by nomadic tribes-Egypt Prehistory

making the transition from hunter-gatherer to semi-permanent settlement and similar structures are still built by modern hunter-gatherer tribes all over the world.

Another striking detail of the Arkin 8 site is the concentration of artifacts in small areas of the “village,” implying that these were areas where groups of people gathered to work on stone artifacts together. Arkin 8 paints a vivid picture of emerging human society.

Another important site is the site labeled BS-14, in the Libyan Desert’s Bir Sahara depression. Today this area is dry and parched, but during the Achulean Period it was nourished by the frequent rainfall. As was mentioned before, Egypt and the surrounding area of this period was subject to much more rainfall than it is now.

The Abbassia Pluvial prevailed during the late Achulean Period, lasting around 30,000 years. During this time, according to the artifacts and remains found at BS-14, the hunter-gatherer culture became more stationary around the permanent water holes.

Women, children, and young men browsed for the bulk of the tribe’s food near the water hole, while the older men would go out and hunt on the grasslands

Middle Paleolithic: 100,000 – 30,000 BC

Between the Lower and Middle Paleolithic eras, the Abbassia Pluvial ended and the Sahara returned to a desert state.

By this time Homo erectus had evolved into Homo neanderthalensis, and began to escape the encroaching desert by migrating to the Nile Valley and to the oases that were left, such as the one at Kharga.

It was about this time that a more efficient stone tool industry developed. Called Levalloisian after the site in France where tools of this style were first discovered, it involves the making of several stone tools from one piece of stone by chipping a number of similarly sized and shaped flakes from around the circumference of the stone.

This technique was a good step over the previous techniques which often required an entire stone to make a single tool, or if multiple flakes were taken from a single stone, they would be of varying sizes, many unusable.

With this technique, numerous thin, sharp, almost identical flakes could be made and only slightly reshaped to make what was desired. The standardization of stone tools, as well as the development of several new tools had begun. Most importantly, the Levalloisian industry resulted in an invention that would change everything that had come before: the spear point.

Levallois points not only had a better piercing point, they were also made to be fitted to wooden shafts. The advantages of a stone spear point over a sharpened wood one permitted a great increase in hunting efficiency, as well as a change in hunting tactics.

The stone spear point may even have led to another trait of the Middle Paleolithic, which was the focus of tribal attention on one particular type of game, such as sheep or goats, a step toward domestication.

It was during Middle Paleolithic times that early humans began to spread throughout the area.

The development of these new stone industries and survival techniques, coupled with the Mousterian Pluvial (which was even greater than the Abbassian that preceded it) between 50,000 and 30,000 BC caused a widespread distribution of early human culture.

Whereas Lower Paleolithic sites are few and far between, Middle Paleolithic sites are scattered all over Egypt and the Sudan,

from the Nile Valley to the coast of the Red Sea to even the now-hostile Liqiya depression in the southern Libyan Desert.

The Mousterian Pluvial caused the Sahara to bloom like never before, not only in vegetation and wildlife, but also in new human settlements. By this time, early humans (still Neanderthaloid) had spread to almost every habitable area of North Africa.

Two new industries emerged during the Mousterian Pluvial, those being the Aterian Industry and the Khormusan Industry.

The Aterian Industry, named for the type site at Bir-el-Ater in Tunisia, began some time around 40,000 BC, about the middle of the pluvial, and ended just shy of 30,000 BC.

Aterian points are characterized by a distinct “tang” or plug on the bottom, which allowed for a more secure fit to the spear shaft.

Originally thought to be arrow points, Aterian points may have been far too bulky to be used on primitive arrows, and were more likely points for a smaller variety of spear, the dart, which was more efficient in hunting small game than the normal-sized spear.

Another invention of the Aterian Industry was that of the spear-thrower,-Egypt Prehistory

a small length of wood with a notch at one end for the back end of the spear shaft, which allowed for greater power in throws as well as greater accuracy.

These new developments permitted increased efficiency in hunting large grazing animals.

The discoveries of gigantic stores of animal remains and human artifacts at site BT-14 attest to the success of these new hunting methods as well as the success of the settlement itself.

The bones from this site reveal that our ancestors made use of a wide variety of animal life such as the white rhinoceros, the now-extinct Pleistocene camel, gazelles, jackals, warthogs, ostriches, and various types of antelopes.

In the Khormusan Industry,

stone tools became even more varied and advanced, and tools made of bone and ground hematite became widespread. Of course, these industries did not follow one another one by one, but rather overlap by several thousand years as well as in area.

The Khormusan is noted above all for the prolific use of a small, sharp point that greatly resembles the early arrow points of the Native Americans. In fact, such points were used during the Upper Paleolithic to tip the arrows developed at that time.

Whether the Khormusans developed bow technology is still under debate, as is whether the Aterians did.

Regardless, the Khormusans were certainly efficient hunters, as well as being gatherers and fishers, and their diet resembled that of the Aterians, and added wild cattle (think of cattle roughly twice as big as our domestic cattle), and fish from the Nile.

These animals came from many different in the Nile Valley and the surrounding area, so Khormusan hunting parties must have ranged from the river itself to the savanna grasslands.

These two industries, or rather, these two cultures, for such they were, existed almost side-by-side until the end of the pluvial, foreshadowing the the great cultural cross-sections that would inhabit Dynastic Egypt thousands of years later.

Upper Paleolithic: 30,000 – 10,000 BC-Egypt Prehistory

Some time around the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, or in the few centuries before it, the Mousterian Pluvial ended and desert once again reclaimed the Sahara region.

Fleeing the desert, many of the peoples settled in the area migrated closer and closer to the Nile. It is possibly during this time that various tribes began to interact, providing a much wider gene pool on which to draw. It is unfortunate that little is known about the period from 40,000 – 17,000 BC. However, it is easy to draw conclusions based on earlier and later events.

The growing barrenness of the Sahara would obviously cause many of the settlements to die of starvation, and once again survival of the human race in this area depended on the Nile. Naturally, some industries would survive and new ones would be created.

These new industries show many similar trends, especially that of the miniaturization of tools, possibly as a desire to conserve resources. Most of the data about this period in time comes from the famous site of Kom Ombo.

Kom Ombo-Egypt Prehistory

is located on the east bank of the Nile in the southern area of Upper Egypt. Archaeologists know that this site is from the Upper Paleolithic because of the existence of burins, small, stubby, pointed tools made of flakes and characterized by long, narrow flakes forming a point. The discovery of burins in Egyptian archaeological sites prompted Edmund Vignard, the discoverer of Kom Ombo, to label it a new industry: the Sebilian.

Sebilian tools-Egypt Prehistory

are manufactured from diorite, a hard, black, igneous rock that was plentiful in the area. The Sebilian Industry is divided into three distinct stages, based on the artifacts created and the techniques used to make them.

Sebilian I, also called Lower Sebilian, is essentially a modified Levallois industry with retouched points and the first burins (small, knobby points). Sebilian II and III are true microblade and burin industries and by this time diorite had given way to the more durable and workable flint.

But even with these developments, Sebilian artifacts appear technologically conservative and backward when compared with some of the Upper Paleolithic industries in Europe.

Complicating everything, however, is the discovery of a coexisting industry now labeled Silsillian (c. 13,000 BC) which effectively puts the early Egyptians back at the forefront of prehistoric technological development.

Sisillian was a highly-developed microblade industry that included truncated blades, blades of unusual shapes made specifically for one task, and most significant of all, a wide variety of bladelets for mounting onto spears, darts, and arrows.

There is almost no trace of earlier techniques such as Levalloisian, and Silsillian blades in some cases are thousands of years ahead of anything found in Europe from this period.

The Silsillian Industry also premiered the creation of microliths. Microliths are small, fine blades used in advanced tools such as arrows, harpoons, and sickles, and since they are smaller, use less material.

This latter development may have been due to the fact that in the Kom Ombo area, high-quality stone was in short supply. Additionally, the fact that these blades were used for agricultural tools such as sickles shows that by this time basic farming had begun, and earlier than had been previously thought.

Unlike their European “contemporaries” who had to deal with the changing post-ice age climate and the disappearance of several food species, the early Egyptians were still able to engage in hunting large game animals, and since many of the animal herds were now concentrated near the Nile, more stable settlements could be made. The Halfan Industry, or rather, the Halfan people, for it was much more than just a way of making tools, flourished between 18,000 and 15,000 BC (though one site has been found dating to before 24,000 BC) on a diet of large herd animals and the Khormusan tradition of fishing. Although there are only a few Halfan sites and they are small in size, there is a greater concentration of artifacts, indicating that this was not a people bound to seasonal wandering, but one that had settled, at least for a time.

Another group that did rather well during this time (17,000 – 15,000 BC) was the Fakhurian, an industry based entirely on microlithic tools. Indeed, they are the only industry discovered so far that is solely microlithic.

Some Fakhurian blades-Egypt Prehistory

are less than 3 cm long! At the same time, the two Idfuan industries were retaining a culture based on nomadic hunting, trapping, and snaring.

During this time, at least in Upper Egypt, there is a trend for industries, as they become more advanced, to become more localized.

No doubt this is due to the fact that the people were ceasing to be nomadic, settling in various areas, and then developing separately from everyone else depending on the environment in which they made their home, whether it was on the banks of the Nile, on the savannas, or in one of the outlying oases not yet claimed by the desert.

Perhaps it should be mentioned that the Nile of the Paleolithic was much different than the Nile of today.

Although dry, the desert areas were not completely hostile, as the annual flooding of the Nile was much higher than today, which resulted in a greater groundwater table and in turn, oases, floodpools, and waterholes.

With the sites from these periods archaeologists begin to see the signs of “true” cultures emerging.

The Qadan (13,000 – 9,000 BC) sites,-Egypt Prehistory

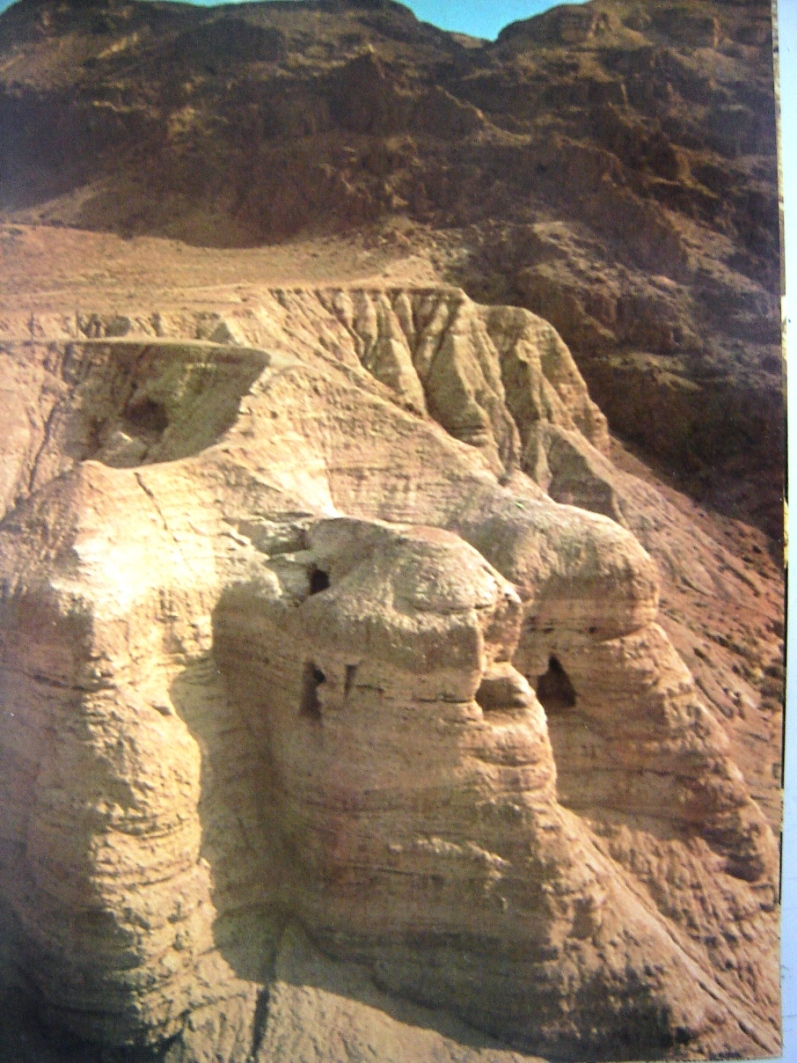

stretching from the Second Cataract of the Nile to Tushka (about 250 km upriver from Aswan, actually have cemeteries and evidence of ritual burial. It is also during this time that the first great experiments in ordered agriculture began.

Grinding stones and blades have been found in great numbers with a glossy film of silica on them, possibly the result of cut grass stems. Sadly, as stone preserves better than straw baskets or satchels, the extent of agriculture from this period can not be determined.

It may not have been true agriculture as we know it, but rather a sort of systematic “caring for” the local plant life (watering and harvesting, but as yet no planting in ordered rows and the like). Yet even this would put the Paleolithic Egyptians on almost the same technological level as the early Neolithic peoples in Europe.

Some of the sites also give evidence that fishing was abandoned by the people living there, possibly because farmed grains (barley, most likely), together with the large herd animals still hunted, created a diet that was more than adequate.

Oddly though, almost as soon as this protoagriculture was developed, it appears to have been abandoned.

Beginning around 10,500 BC, the stone sickles that were so predominant seem to simply fade out of the picture and there is a return to the hunter-gatherer-fisher culture that came before.

Invasion by another people is a possible explanation, though a series of natural disasters that devastated the fledgling crops is more logical, as we are dealing with abandonment by not one, but many prehistoric societies over a widespread area.

At first it would seem that the growing aridity of the environment was the cause.

Certainly, given the present state of the Sahara and the surrounding area, this is a logical conclusion, but new evidence shows that this period was marked by a series of rather severe and violent Nile floods which could have destroyed the “farmlands” and discouraged the people from continuing to rely on crops as a dietary index.

It was about this time that the demise of the various Paleolithic peoples in Egypt began. It may very well be that the abandonment of protoagriculture contributed to this, but the discovery of the Jebel Sahaba cemetery sheds some new light on the end of many Paleolithic cultures.

In all, three Qadan cemeteries are known: one at Tushka,-Egypt Prehistory

and two at Jebel Sahaba, one on each side of the river. Although many of the remains unearthed at these sites are the usual cross-section of elderly and young, chieftains and commoners, there are quite a disturbing number of bodies from the final 10,000 years of the Upper Paleolithic that appear to have died by violence.

Stone points found with the remains were almost all located in areas of the body that suggests penetration as spear points or similar weapons. Most were located in the chest and back area, with others in the lower abdomen, and even a few entering the skull through the lower jaw or neck area! Additionally, the lack of bony calluses as a result of healing near these points shows that in many of these cases the wound was fatal (bone tissue repairs itself rather quickly, preliminary healing often begins before even that of soft tissues).

A statistical analysis of the main cemetery at Jebel Sahaba gives a figure of 40 percent of the people buried there died from wounds due to thrown projectiles; spears, darts, and arrows.

Why then was a hunter-gatherer culture so prone to violence? One explanation is diminishing resources, caused by the growing aridity and the failure of the protoagriculture experiments.

The Jebel Sahaba cemeteries-Egypt Prehistory

must only have been used for a few generations and for that many violent deaths to occur within that time supports an explanation based on massive intertribal warfare.

Also, since the victims were of all ages (except infants; only one infant is buried in each of the Jebel Sahaba cemeteries), this could indicate that the majority of the skirmishes were actually based on raiding and ambush, as “normal” warfare usually only involves young to middle-aged males. And we should not dismiss the possibility of invasion by a more advanced, or at least more powerful, people from outside, especially if Jebel Sahaba and similar sites date to as late as 7000 BC, as by then the people would have been in competition with larger and more advanced Epipaleolithic cultures.

Epipaleolithic: 10,000 – c. 5,500 BC-Egypt Prehistory

The Epipaleolithic years are largely a transition between the Paleolithic and the Predynastic time periods in ancient Egypt, a time between the hunter-gatherers of before and the appearance of the true farming of the village-dwelling cultures after 5500 BC.

Most of the information from this era comes from the site of El Kab, nestled between the eastern bank of the Nile and the Red Sea Hills. Before the discoveries at El Kab, it was thought that Paleolithic artifacts, even those dating to the Epipaleolithic, would not be found on the floodplain of the Nile, simply because of the action of the inundation.

However, in the case of many of the artifact sites, it was the inundation that preserved them, as the Nile deposited layer upon layer of soil each year without washing the artifacts away.

Three major “camps” of Epipaleolithic peoples were discovered, the oldest dating to around 6400 BC, the one above it to 6040 BC, and the uppermost to 5980 BC.

The importance of this site can easily be seen in the fact that the major archaeologist of the site, Dr. Paul Vermeersch, classified over 4,000 artifacts. Most of these were artfully made and minutely detailed microblades.

Beads made of ostrich shell were also discovered,

showing that even then the ancient Egyptians had a love for ornamentation. Burins, scrapers, and points of all sizes and description rounded out the inventory.

The camps at El Kab were most likely occupied only during spring and summer. The annual inundation of the Nile, especially given how massive it was then, would make it next to impossible to live in those locations year round. It is apparent that these tribes were still largely nomadic. Despite this, the camps (for such we should label them) enjoyed many times of prosperity, living near the cool Nile and benefiting from its supply of fish, supplemented by the traditional hunting of savanna wildlife such as wild cattle and gazelles.

The two most prominent industries at this time, as discovered near Wadi Halfa in the northern Sudan, were the Arkinian and the Sharmarkian. So far, Arkinian artifacts have only been found at one site and have been dated to around 7440 BC. The site is a small settlement, with possibly around thirteen dwellings, given the concentration of debris in a clustered location.

Like many of the settlements at this time near the Nile, this was most likely a seasonal camp of some kind, though we will have to wait until other Arkinian sites are discovered. Arkinian was largely a microlithic industry, making use of very small, skillfully crafted stone tools, but large blades and a new method of extracting more material from a stone, the double-platform core, have been found.

We know more about the Sharmarkian industry than the Arkinian. A newer industry, but one that spans a much larger time period, Sharmarkian artifacts have been dated from 5750 BC to 3270 BC, if not even more recent.

Although more prolific, the Sharmarkian artifacts actually show a decline in the quality of toolcraft toward the end of the Sharmarkian. Settlements of these people have been found on the beaches of soil left by the inundation.

These seasonal camps merged together and grew into large concentrations of dwellings over time. There is evidence in these later Epipaleolithic sites of a population explosion around 5500 BC, possibly due to the development of true agriculture as well as animal domestication.

In a very short time, geologically speaking, the people had gone from savanna nomads to riverdwellers, making a very efficient adaptation to the new environment.

Unfortunately, we still do not know exactly when agriculture and animal domestication were discovered (or introduced by another people) in Egypt.

There is an odd gap of around a thousand years between these riverine settlements of the late Epipaleolithic and the true farming villages of the Predynastic cultures during which great strides in Egyptian knowledge were made.

It is even surmised that it was during this time that they began to develop the writing systems that would evolve into the hieroglyphs.

There are sites in Nubia that possess possible remains of domesticated animals that date to around 5110 BC. Whether domestication was brought into Egypt or was discovered within her borders is still a debated topic.

All things aside, this final time period before the Predynastic age remains a very important problem for researchers. Each new discovery, though, sheds more light on the history of the first Egyptians.

Predynastic (5,500 – 3,100 BC)-Egypt Prehistory

Beginning just before the Predynastic period, Egyptian culture was already beginning to resemble greatly the Pharaonic ages that would soon come after, and rapidly at that.

In a transition period of a thousand years (about which little is still known), nearly all the archetypal characteristics appeared, and beginning in 5500 BC we find evidence of organized, permanent settlements focused around agriculture. Hunting was no longer a major support for existence now that the Egyptian diet was made up of domesticated cattle, sheep, pigs and goats, as well as cereal grains such as wheat and barley.

Artifacts of stone were supplemented by those of metal, and the crafts of basketry, pottery, weaving, and the tanning of animal hides became part of the daily life.

The transition from primitive nomadic tribes to traditional civilization was nearly complete.

One of the most interesting aspects of the transition period is the shift in burial customs.

Previous to the permanent settlements, most burials were done where it was convenient, often in a centrally-located cemetery near to or inside the settlement, such as the cemeteries at Jebel Sahaba.

As the seasonal hunting camps grew into more stable agricultural villages, burial sites and practices changed.

Cemeteries and single graves were no longer located near the living, but were placed further and further away, both from the villages as well as the cultivated land, most often on the very edge of what would be considered the village’s “territory.” Even children, formerly buried under the floor of their home, were now relegated to these outer cemeteries.

The reasons for this are unknown, but a growing feeling of necrophobia, a fear of the dead, might be the cause, as is often the case in many cultures. Practices too, changed.

Here we see the beginnings of the “life after death” beliefs that centuries later, would make the ancient Egyptians famous.

The dead were buried with provisions for the journey into the next life, as well as pottery, jewelry, and other artifacts to help them enjoy it.

Offerings of cereals, dried meat, and fruit were included, but hunting and farming implements were also common (presumably so the dead would not starve after having eaten all the offerings).

Even then, the Egyptians believed that the next life would be very much like this one. Interestingly enough, the dead were buried in a fetal position, surrounded by the burial offerings and artifacts, facing west, all prepared for the journey to the world of the dead, where the sun shone after leaving the world of the living.

The Chalcolithic period,

also called the “Primitive” Predynastic, marks the beginning of the true Predynastic cultures both in the north and in the south. The southern cultures, particularly that of the Badarian, were almost completely agrarian (farmers), but their northern counterparts, such as the Faiyum who were oasis dwellers, still relied on hunting and fishing for the majority of their diet. Predictably, the various craftworks developed along further lines at a rapid pace.

Stoneworking, particularly that involved in the making of blades and points, reached a level almost that of the Old Kingdom industries that would follow. Furniture too, was a major object of creation, again, many artifacts already resembling what would come.

Objects began to be made not only with a function, but also with an aesthetic value. Pottery was painted and decorated, particularly the black-topped clay pots and vases that this era is noted for; bone and ivory combs, figurines, and tableware, are found in great numbers, as is jewelry of all types and materials.

It would seem that while the rest of the world at large was still in the darkness of primitivism, the Predynastic Egyptians were already creating a world of beauty.

Somewhere around 4500 BC is the start of the “Old” Predynastic, also known as the Amratian period, or simply as Naqada I, as most of the sites from this period date to around the same time as the occupation of the Naqada site.

The change that is easiest to see in this period is in the pottery. Whereas before ceramics were decorated with simple bands of paint, these have clever geometric designs inspired by the world around the artist, as well as pictures of animals, either painted on or carved into the surface of the vessel.

Shapes too, became more varied, both for practical reasons depending on what the vessel was used for, and aesthetic reasons.

Decorative clay objects were also popular, particularly the “dancer” figurines, small painted figures of women with upraised arms.

Yet perhaps the most important detail of all about this period is the development of true architecture. Like most of Egyptian culture, we have gleaned much of our knowledge from what the deceased were buried with, and in this case, we have several clay models of houses discovered in the graves that resemble the rectangular clay brick homes of the Old Kingdom. This shows that the idea of individual dwellings, towns, and “urban planning” started around 4500 BC!

The third stage of the Predynastic period is dated to around 4000 BC and is labeled the Gerzean period or Naqada II. Amratian and Gerzean are vastly different from one another, and one can see the growing influence of the peoples of the North on those of the South. Soon this would result in a truly mixed people and culture, that of the Late Predynastic, or Naqada III.

greatest difference between the Amratian and the Gerzean peoples can be seen in their ceramics industries.

While Amratian pottery did have some decorative aspects, its primary purpose was functional. Gerzean pottery, on the other hand, was developed along decorative lines.

Gerzean pottery

is adorned with organic-inspired geometric motifs, and highly realistic depictions of animals, people, and the many other things that surrounded the Gerzean people.

There are more than a few surprises in the motifs, however.

Unusual animals such as ostriches and ibexes give clues to a possibility that the Gerzeans hunted in the sub-desert, as such animals were not to be found near the Nile.

We also find what are possibly the first representations of gods, almost always shown riding in boats and carrying standards that greatly resemble the later standards that would represent the various provinces of Egypt.

It is possible too, that these are simply some form of historical records (visits of chieftains, battles, perhaps?), but as they are almost always painted on votive artifacts buried with the dead, the plausible explanation points to the sacred.

When compared to the Pharaonic periods, the Gerzean culture is not much dissimilar, having reached a high level of civilization, especially in is religious aspects, and particularly in those dealing with funerary customs.

Amratian burials were most often simply a pit in the ground, covered over by a skin-covered framework, but with the Gerzean, tomb-building became a foreshadowing of what was to come, with furnished underground rooms, near replicas of the dwelling that the deceased had occupied in life. Amulets and other ceremonial objects, many of which depict the early animal-form gods of the Gerzeans, are also prolific in these tombs. The Gerzean form of the afterlife would eventually grow into the Cult of Osiris and the magnificent burials of the Dynasties.

Previously it was believed that the transition between Predynastic and Dynastic was the result of a brutal series of revolutions and warfare brought about as a result of the discovery of metallurgy and the new social structures such as cities, individual dwellings, and writing.

Yet as more and more details of this time period are uncovered, we see that it was nothing of the sort, but rather the slow process of technological evolution.

The above-mentioned new technologies could be Mesopotamian in origin, as they are found there earlier than they are in Egypt, yet there is little proof of this.

About the only Mesopotamian artifacts found in Egypt proper are cylinder seals, and these only point to a strictly commercial-political connection.

A few artifacts of Egyptian origin do bear Mesopotamian design traits, but again, this could be the result of an eager artist copying an imported artifact.

It is of course their writing system that is the Egyptian hallmark, but where did it begin, and when? Some have said that writing was imported, but after a brief study of the motifs found on ceramics from the Naqada periods we can discard this as only a remote possibility.

The pottery motifs evolve distinctly over a period of time into a regular set of images that greatly resemble the traditional hieroglyphics.

Already they show the fundamental principle of hieroglyphic writing, that of the combination of pictograms and phonograms.

A pictogram is an actual representation of the item it represents. In such a system, the pictogram for a man is a picture of a human figure, the pictogram for water is a picture of water.

A phonogram is a picture that stands not for its image, but for a sound or set of sounds. For example, the picture of a water bird might mean sa, and the word sa would not mean “bird” but “child,” or sa even might be combined with other phonograms to create a larger word. Such systems of writing exist even today.

Japanese, with its combination of a phonetic alphabet with a set of complex characters that can mean either a sound or an entire word, is a perfect example. These symbols found on pottery and other artifacts of the Amratian period might be writing, but by the Gerzean they most definitely are a form of writing.

No time of the Predynastic offers as many questions as the period of unification of southern and northern Egypt. Exactly who conquered whom is the first.

Many sources point to the event as the victory of the south over the north, yet the resulting social system resembles more that of the north than the south. Kurt Sethe and Hermann Kees, among the first to draw conclusions about this period came up with a combination of both theories: that Egypt was first unified under the north, but for one reason or another collapsed and the power was picked up by the southern kings, who kept the original form of government set up by the north. Recent archaeological evidence is beginning to discredit this, but it still seems to be among the most logical explanations.

Another theory is that the south conquered the north, but adopted much of the northern culture into their own. This is not unusual in the least when dealing with Egypt. The Ptolemies were the Greek rulers of Egypt after Alexander the Great, yet they absorbed as much of the Egyptian culture as they could, calling themselves Pharaohs and even being buried according to Egyptian custom instead of Greek.

Exactly who the first king of unified Egypt was is also difficult to say, or even when the actual unification occurred. The most powerful piece of data on this event is the Narmer Palette, a triangular piece of black basalt depicting a king whose name is given as Nar-Mer in the hieroglyphs.

On the obverse he is shown wearing the white crown of the south and holding a mace about to crush the head of a northern foe, and on the reverse, the same figure is shown wearing the red crown of the north while a bull (a symbol of the pharaoh’s power) rages below him, smashing the walls of a city and trampling yet another foe.

Another artifact, the “Scorpion” Macehead, depicts a similar figure, only this time the name is given by the pictogram of a scorpion.

This king-figure is called in many documents alternatively Narmer, or Aha, and if the historian Eratosthenes is to be believed, this is the legendary king Meni, or Menes. Whether “King Scorpion” is the same person as Narmer is a bit of contention, but the two are widely accepted to be the same.

If these two artifacts, and others like them from the same period, do in fact depict this as the first king of unified Egypt, then the date for the Unification can be placed sometime between 3150 and 3110 BC.

With the onset of the last great ice age about 30,000 years ago huge glaciers formed on the high African mountains of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. When the great global meltdown began about 12,000 years ago these huge glaciers sent massive volumes of water to the north. The gigantic discharges flowed out of Lake Victoria and down the Blue and White Nile valley basins. Catastrophic floods filled the lower Egyptian valley, washing away all villages and burying their shattered remnants in sediment, thus breaking the continuity of human life in Egypt. Archaeologist today call this the “Wild Nile.”

Seasonal heavy floods held the Nile valley in its grip for more than three thousand years. During this period human occupation was impossible. Then, as the glacial melting slowed the valley became suitable to human settlement once again. The glaciers continued to melt through the millennia, until today very little is left of them.

The Sahara saw repeated wet and arid cycles that follow the ice ages over the past five hundred thousand years.

During the wet cycles the Sahara saw much human occupation, when the desert “blossomed like the rose.” After the last ice age the region once again was occupied.

However, melting of the world ice sheets caused a northward shift of the monsoon belt, creating increasingly arid conditions in the once verdant Sahara regions.

The peak of human occupation in the Western Desert took place between 6,500 and 4,700 BC, when weather conditions forced abandonment of those areas. The final desiccation of the Sahara was not complete until the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Many archaeologists believe those people migrated south to sub-Saharan Africa, or to the Nile valley, the environment of which greatly improved as it dried out from the previous heavy flooding.

Refer to previous discussion by the Urantia Papers.

One site in upper Egypt, out of reach of the wild river inundations, showed the gathering of large quantities of fish, and preservation through smoking.

Some cemeteries in this southern region show an exceptionally high rate of injury caused by stone weapons, suggesting that the dramatic climate changes were affecting human food supplies and survival.

Meanwhile, virtually no evidence exists for human occupation in the Nile valley between 10,000 and 6,000 BC except for a group of very small sites around 9,400 BC at the second cataract.

A hiatus in radiocarbon dates suggests the valley was barren of settlements during that period. Then human groups again began to enter the valley.

Some may have come off the Sahara plateau. Others may have come from the Levant via the Mediterranean. Still others were Andite, coming from Mesopotamian regions and overland from the Red Sea.

The illustration below shows relative chronology for Egypt and neighboring regions after the Great Deglaciation. The Table is from Ancient Egypt, A Social History, B. G. Trigger, B. J. Kemp, D. O’Connor, A. B. Lloyd, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

This chart can be compared with the following table, borrowed from the web site of Francesco Raffael.

Period – years

Phase (Kaiser)

Tombs – Other objects – Rulers

Suggested Sequence

Amratian

(c. 3900)

Naqada Iabc, IIa

(Abydos tomb U-239)

(Hierakonpolis Loc. 6, tombs 3, 6)

B-, P-, C- class pottery

Early rhomboidal palettes, undecorated or with incised drawings

Gerzean

(c. 3600)

Naqada IIb

Decorated Pottery (D-class)

(Naqada tomb 1411, T4)

Gebelein painted cloth (IIc?)

From rhomboidal shapes to fusiform, with appendices and animal heads on the edge

Naqada IIc/d1,2

Wavy handled pottery (W-class)

Brooklyn, Carnarvon knife handles (Naqada IIc-IIIa)

(NOTE: Abu Zeidan t.32, which contained the Brooklyn knife-handle, dates early Naqada III)

(Hierakonpolis tomb 100).

(Abydos t. U-q, U-547; knife handle in t. U-503 and fragments from U-127)

Zoomorphous palettes

(fishes, turtles, mammals)

Ostrich palette

Gerzeh palette

Min palette

Late Predynastic

(c. 3300)

Naqada IIIa1,2

(Hierakonpolis Loc. 6, tomb 11)

Scorpion I (Abydos tomb U-j)

Louvre palette

Oxford palette

Hunters palette

DYNASTY 0

Naqada IIIb1

(Seyala tomb 137.1; Qustul tomb L24)

Horizon A

Anonymous Serekhs, Double Falcon,

Ny-Hor, Pe-Hor, Hat-Hor, Hedj-Hor; (Iry-Hor)

(Gebel Sheikh Suleiman graffito)

(Hierakonpolis Loc. 6, tomb 10)

Metropolitan Mus. palette

Battlefield (Vultures) palette

Bull palette

Tehenu palette

Plover palette

Narmer Palette

(end of Narmer’s reign c.3000)

Protodynastic

(c. 3150-3000)

Naqada IIIb2/c1

Horizon B

Tarkhan Crocodile, Hk (?) Scorpion II, Abydos: Iry Hor, Ka, Narmer

(Hierakonpolis Loc. 6, tomb 1)

The archaeological evidence shows two different emerging cultures, one in the Delta, and one in upper Egypt, centered around the great bend in the Nile, the location of modern Qina, and overland routes from the Red Sea locations now known as Bur Safajah and Al Qusayr. These routes of travel between the Nile and the Red Sea have been known since ancient times. Radiocarbon dating suggests the settlements in the Delta may somewhat predate those in upper Egypt.

If agriculture was known in Anatolia and other regions of the Near East in the Natufian cultures from 9,000 BC, and if the Nile was resettled by immigrants from those regions, we should expect that they brought agriculture and animal herding with them.

The Nile valley did not exist in grand isolation from the rest of the world, even though many Egyptologists are oriented to that frame of mind. Evidence suggests that horticultural in small, local groups may have traveled southward along the Nile from the Delta into nearby oases and the Sudan. However, penetration of such horticulture may also have come overland from the Red Sea. Several of the basic food plants that were grown are native to the Near East.

Large-scale migrations were not necessary to introduce this influence. We should also remember that the evidence from the Wadi Kubbaniya shows agriculture in Egypt before the great ice age deglaciation.

Although direct evidence for agriculture and animal herding has not yet been found for this early period controversy exists. Grinding stones, usually associated with grain production, and hence farming, were discovered. Unable to credit agriculture at this date some archeologists presume that the people ground harvested wild plants! (Note earlier discussion that showed the plants could not be processed through grinding.) Decorated potsherds are also found at these sites, showing a more cultured way of life. The construction of wells, slab-lined houses, and wattle-and-daub buildings show a permanent populace, only possible with an adequate supply of food.

Much dispute exists about the possible of influence of different areas of the Near East. Some favor the Levant, and countries along the eastern Mediterranean shores. Others propose origins in Mesopotamian regions. The first possibility is preferred by many archaeologists because they believe the earliest known Neolithic cultures in Egypt were found at Marimda Bani Salama, on the southwest edge of the Delta, and farther to the southwest, in the Fayyum lake region. The site at Marimda, which dates to the 6th-5th millennia BC, gives evidence of settlement and shows that cereals were grown. In the Fayyum the settlements were near the shore of Lake Qarun, where the settlers also engaged in fishing. Marimda is a very large site that was occupied for many centuries. The inhabitants lived in lightly-built huts and used pottery. But other sites have been identified in the Western Desert, in the Second Cataract area, and north of Khartoum. Some of these Neolithic sites are as early as those in the Delta, while others overlapped with the succeeding Egyptian predynastic cultures. Hence the origin and chronology of the inhabitants of the Egyptian region are not clear from present knowledge.

In Upper Egypt, between Asyut and Luxor, remains of the Badarian cultures date from the mid 5th millennium BC. This culture was located on the east bank of the Nile River at al-Badari and at Deir Tasa. British excavations there during the 1920s revealed settlements and cemeteries dating to about 4000 BC, or earlier.

The existence of a still earlier culture, called the Tasian, as a chronologically or culturally separate unit has not been demonstrated beyond doubt. Precise separation of the cultures has not been determined; they may have coexisted, or may have blended one with the other. Tasian remains are somewhat intermingled with the materials of the subsequent Badarian stage, and, although the total absence of metal and the more primitive appearance of its pottery would seem to argue for an earlier date, it is also possible that the Tasian was contemporary with the Badarian. Remains indicate that the Tasians/Badarians were settled farmers who cultivated emmer wheat and barley and raised herds of sheep and goats. The dead were usually buried in straw coffins, with the bodies in crouching or bent positions, head to the south, face looking west. Most Egyptologists today consider the Tasian to be simply part of the Badarian Culture, with the differentiation perhaps originating in the desire for fame by the excavators.

Most of the evidence for the Badarian/Tasian culture comes from cemeteries, where the burials included pottery, ornaments, some copper objects, and glazed steatite beads. The most characteristic predynastic luxury objects, slate palettes for grinding cosmetics, occur for the first time in this period. The artistic and technical skills of the Badarians continually improved over the centuries. While the early excavations in the 1920’s thought of the Badarians as limited to one site, later work showed them all along the Nile valley in Upper Egypt. Material remains include combs and spoons of ivory, female figurines, and copper and stone beads. Badarian materials have also been found at Jazirat Armant, al-Hammamiyah, Hierakonpolis (modern Kawm al-Ahmar), al-Matmar, and Tall al-Kawm al-Kabir.

The pottery of the Badarian Period is distinguished by a black top with red body. It was extremely thin-walled and well-baked; many regard it as the best ever made in the Nile River valley. The firing was probably done in a rudimentary kiln with the pottery and fuel piled together and then covered with animal dung. Pottery making at this stage is thought to have been a cottage industry with some local specialization. Badarian pottery is found in three main types which gradually change over time, and which continued to be produced in later periods: red-polished ware (called P-ware), black-polishedware (called BP-ware), and black-topped red-polished ware (called B-ware). The B-ware pottery is the most distinctive of the early Predynastic pottery types. The irregular black top and interior of B-ware is thought to have been produced by placing the red-hot vessel in the burning embers of a fire. They are all handmade using the coil method, since the slow wheel was not introduced into Egypt until later. The jars have very hard, thin walls but the shapes are still fairly basic, confined mainly to open bowls at this stage. Some vessels were decorated with prominent ribbing, while others are burnished. A rippling effect was sometimes produced by trailing a serrated bone or comb over the surface before firing. Some finer vessels were decorated with incised designs of palm fronds or six-rayed stars.

The economy was based on agriculture and animal husbandry. Settlement sites show small villages or hamlets.

The origins of this culture are problematic. Based on the limited evidence of pottery and grave goods archaeologists cannot reach a consensus whether the new culture was completely foreign to the Nile Valley or whether it represents an adaptation of new ideas and technologies by the indigenous people. Different archeologists have looked north, south, east, and west. Many believe it did not develop from a single source. The presence of Red Sea shells in graves shows commerce to the east. Since no Badarian culture is evident from the lower Nile the contacts must have come over land routes from the Red Sea. Refer to Chapter 2 on Egyptian Prehistory in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Ian Shaw, Editor, Oxford University Press, 2000.

For a long time the Badarian was considered to have emerged from the south, because it was thought that the Badarians had poor knowledge of chert, which would show that they came from the non-calcareous part of Egypt to the south; on the other hand, the origins of agriculture and animal husbandry were assumed to lie in the Near East. The theory that the Badarian originated in the south is, however, no longer accepted. The selection of chert is perfectly logical for the Badarian lithic technology, which seems to show links with the Late Neolithic from the Western Desert.

The rippled pottery, one of the most characteristic features of the Badarian, probably developed from burnished and smudged pottery, which is present both in late Sahara Neolithic sites and from Merimda in the north to the Khartoum Neolithic sites in the south. Rippled pottery may thus have been a local development of a Saharan tradition.

The Badarian culture may have been characterized by regional differences, the unit in the Badari region itself being the only one that has so far been properly investigated or attested. On the other hand, a more or less uniform Badarian culture may have been represented over the whole area between Badari and Hierakonpolis, but, since the development of the Naqada culture took place more to the south, it seems quite possible that the Badarian survived for a longer time in the Badari region itself.

The evidence suggests that the Badarian culture did not appear from a single source, although many archeologists prefer the Western Desert as the predominant one. On the other hand, the provenance of domesticated plants remains controversial: an origin in the Levant, via the Lower Egyptian Faiyum and Merimda cultures, might be possible.

See also the article on Predynastic Development in Upper Egypt in the proceedings of the Polish Academy of Sciences on the 1984 Poznan conference, Origin and Early Development of Food-Producing Cultures in North-Eastern Africa, Poznan, 1984. Tomas R. Hays stated:

The origin of the Badarian is not known, but influence from the Near East has been suspected (Frankfort, 1951, Kantor, 1965). Brunton and Caton-Thompson (1928) suggested that the Predynastic Egyptians were not indigenous, but possibly arrivals from the Red Sea. The idea of intrusion of people into the Nile Valley has been repeated by more recent workers.

That these “Neolithic” groups came from outside the Nile Valley is generally accepted, but their origin has been placed in the east (Kantor, 1965), west (Hassan et al., 1980), and south. Baumgartel (1965) and Arkell and Ucko (1965) postulated that the origins may be found in the Sudan.

Hays evaluated pottery from various surrounding sites outside the Nile valley. He concluded that the pottery styles moved from the Central Sudan and Nubia, with a contribution from the Western Desert. He sees this evolution continuing from about 6,000 BC.

Strong evidence argues against origin of the Badarian people from the south. Although influences in ceramic styles and techniques may have come from various areas, and been incorporated into their pottery, this does not mean the people came from those areas. More than a hundred years ago Flinders Petrie recognized the genetic traits of the Naqada people. They had “white” or “yellow” skins, and red, blond, or brown curly hair. He compared them to the Amorites and Libyans. See Naqada and Ballas, Arris and Phillips, Ltd, Warminster, 1896. By Amorites and Libyans he meant fair people with features similar to those found in many areas of Europe today. After exposing literally thousands of bodies that had been preserved in the hot Egyptian sands he could well testify to their racial features.

The chronological position of the Badarian Culture as a precursor to the more recent Naqada Culture is now clearly established through excavation at the stratified site of North Spur Hammamiya. In fact, the available evidence shows that one culture flowed into the next, as a social evolutionary process. For a long time it was thought that the Badarian Culture remained restricted to the Badari region. Characteristic Badari finds however have also been found much further to the south at Mahgar Dendera, Armant, Elkab and Hierakonpolis and also to the east in the Wadi Hammamat. The widespread cultural dispersion along the Nile valley provides some insight into the influence of these people as genetic ancestors to the later Egyptians.

Refer to later discussion on Race.

We also know that substantial travel of people across the Eastern Desert from the Red Sea is attested by petroglyphs in the mountains between the Red Sea and the Nile showing sea-faring boats.

Refer to later discussion on Boats

Refer also to my previous discussion that shows cultures in the Nile valley at this early date had to come from the outside. No indigenous cultures could have survived the “wild Nile.”

This culture began the onset of influences in the Nile valley which forever determined her future.

Wendy Anderson, in a paper entitle Badarian Burial: Evidence of Social Inequality in Middle Egypt During the Predynastic Era, JARCE, XXIX, 1992, showed that an elite social status was recognized at this early date. Cemeteries tended to be segregated according to wealth. Grave goods were status symbols, with the wealthier citizens accorded larger quantities of gifts to accompany them in the afterlife. This practice follows that of people all over the world, which equates lavish burials with high social rank. As stated by Anderson:

The most richly furnished graves were restricted to a minority of the mortuary population, and futhermore, such tombs were subject to plundering. (This information) may be interpreted as a manifestation of the unequal distribution of material wealth amongst the grave occupants and thus an indication of differential access to resources by members of the same Badarian community.

Anderson goes on to comment about differentiation of grave goods that suggests a more complex arrangement of difference social positions, not merely an “elite” separated from “commoners.” Her analysis of several different burial statuses indicated several different social positions. However, she shows that a general analysis of the excavations, involving eighteen cemeteries, reflected a bimodal division of graves with ninety-two per cent of “poor” individuals, and eight per cent who were “wealthy.” She also noted that there was a definite increase in grave goods over time, reflecting a general increase in the general wealth of the communities.

While the evidence suggests this was a limited practice at that point in Egyptian prehistory it became increasingly important throughout the subsequent Naqada Period. Curiously, the Badarian children and young people were given a large number of grave goods, while some adults had none at all. Since the pottery and other artifacts had an economic value this practice may have been dictated by relative lack of wealth, with compassion being exhibited to younger members of the groups. Anderson, Petrie, and others noted that plundering of the grave goods took place shortly after burial while their content was still known, suggesting again that the grave goods had important economic value. As the centuries passed the increasing number of grave goods showed an increase in relative wealth. Also, during the Naqada period some graves became larger and more elaborate, until this social process evolved into mastabas and eventually the pyramid tombs.

Despite the existence of some excavated settlement sites the Badarian Culture is mostly known from cemeteries in the low desert along the east bank of the Nile. All graves are simply pit burials often incorporating a mat on which the body was placed. As was customary in early Egypt, bodies were placed in a contracted position on the left side and with the head to the south looking west. The hands were placed in front of the face or under the cheek. See my web page on Ginger. This practice continued until well into the Dynastic period for commoners. Curiously, and for unknown reasons, in the Early Predynastic period about 15% of the bodies have a head orientation to the north. In the Middle Predynastic this became 98% to the south with only 2% to the north, and then changed back again in early dynastic times.

Other cultural differentiation began to develop as the Badarian evolved into the Naqada phases. Naqadah I sites, named after the major site of Naqadah on the west bank, but also called Amratian after al-‘Amirah, is a distinct phase that succeeded Badarian and has been found as far south as Kawm al-Ahmar (Hierakonpolis; ancient Egyptian Nekhen), near the sandstone barrier of Jabal al-Silsila, which was the cultural boundary of Egypt in predynastic times. Naqadah I differs from Badarian in its density of settlement and in the typology of its material culture, but hardly at all in the social organization implied by finds. In other words, it had the same cultural dynamic but was evolving in its material techniques. Burials continued to follow the Tasian/Badarian practice in shallow pits in which the heads were laid to the south facing west, in a contracted womb position. This burial practice continued throughout the early periods, and into dynastic times. Notable types of material found in graves are fine pottery decorated with representational designs in white on red, figurines of men and women, and hard stone mace-heads that are the precursors of important late predynastic objects.

The evolution of Egyptian society from the Tasian-Badarian groups to dynastic times was extremely rapid.

Naqadah II, also known as Gerzean after al-Girza, is the most important predynastic culture. The heartland of its development was the same as that of Naqadah I, but it spread gradually up and down the Nile valley. These sites have a long span, continuing as late as the Egyptian Early Dynastic Period, circa 3,000 BC. During Naqadah II, large sites developed at Kawm al-Ahmar, Naqadah, and Abydos, showing by their size the concentration of settlement, as well as exhibiting increasing differentiation in wealth and status. Few Naqadian sites have been identified between Asyut and the Fayyum. Near modern Cairo, at al-‘Umari, Ma’adi, and Wadi Digla, and stretching as far south as the latitude of the Fayyum, are sites of a separate, contemporary culture. Ma’adi was an extensive settlement that traded with the Near East. In this period, imports of lapis lazuli provide evidence that trade networks extended as far afield as Afghanistan.

The material culture of Naqadah II included increasing numbers of prestige objects. The characteristic mortuary pottery is made of buff desert clay, principally from around Qina, and is decorated in red with pictures of uncertain meaning showing boats, animals, and scenes with human figures. Stone vases, many made of hard stones that come from remote areas of the Eastern Desert, are common and of remarkable quality, and cosmetic palettes display elaborate designs, with outlines in the form of animals, birds, or fish. Flint was worked with extraordinary skill to produce large ceremonial knives of a type that continued in use during dynastic times.

Sites of late Naqadah II (sometimes termed Naqadah III) are found throughout Egypt, including the Memphite area of upper Egypt and the Delta, and appear to have replaced the local Lower Egyptian cultures. Links with the Near East intensified and some distinctively Mesopotamian motifs and objects were briefly in fashion in Egypt. The cultural unification of the country probably accompanied a political unification, but this cannot be reconstructed in detail. In an intermediate stage, local states may have formed at Kawm al-Ahmar, Naqadah, and Abydos, and in the Delta at such sites as Buto (modern Tall al-Fara’in) and Sais. Ultimately, Abydos became preeminent; its late predynastic cemetery of Umm al-Qa’ab was extended to form the burial place of the kings of the 1st dynasty. In the latest predynastic period, objects bearing written symbols of royalty were deposited throughout the country, and primitive writing also appeared in marks on pottery. Because the basic symbol for the king, a falcon on a decorated palace facade, hardly varies, these objects are thought to have belonged to a single line of kings or a single state, and not to a set of small states. However, the falcon symbol may have universally portrayed the concept of kingship and does not necessarily relate directly to pharaonic descent. This symbol became the royal Horus name, the first element in a king’s titulary, which presented the reigning king as the manifestation of an aspect of the god Horus, the leading god of the country. Over the next few centuries several further symbolic definitions of the king’s position were added to this one.

At this time Egypt seems to have been a state unified under single kings and the first bureaucratic administration. These kings may correspond with a set of names preserved on the Palermo Stone, but no direct identification can be made of them. The latest was probably Narmer, whose name has been found near Memphis, at Abydos, on a ceremonial palette and mace-head from Kawm al-Ahmar, and at the Palestinian sites of Tall Gat and ‘Arad. The relief scenes on the palette show him wearing the two chief crowns of Egypt and defeating northern enemies, but these probably are stereotyped symbols of the king’s power and role and not records of specific events of his reign. They demonstrate that the position of the king in society and its presentation in mixed pictorial and written form had been elaborated by this date.

During this social evolution Egyptian artistic style and conventions were formulated, together with writing. The process led to a complete and remarkably rapid transformation of material culture, so that many dynastic Egyptian prestige objects hardly resemble their forerunners several hundreds years earlier.

A new era began in Egypt with the arrival in Al Fustat in 868 of Ahmad ibn Tulun as governor on behalf of his stepfather, Bayakbah, a chamberlain in Baghdad to whom Caliph Al Mutazz had granted Egypt as a fief. Ahmad ibn Tulun inaugurated the autonomy of Egypt and, with the succession of his son, Khumarawayh, to power, established the principle of locally based hereditary rule. Autonomy greatly benefited Egypt because the local dynasty halted or reduced the drain of revenue from the country to Baghdad. The Tulinid state ended in 905 when imperial troops entered Al Fustat. For the next thirty years, Egypt was again under the direct control of the central government in Baghdad.

The next autonomous dynasty in Egypt, the Ikhshidid, was founded by Muhammad ibn Tughj, who arrived as governor in 935. The dynasty’s name comes from the title of Ikhshid given to Tughj by the caliph. This dynasty ruled Egypt until the Fatimid conquest of 969.

The Tulinids and the Ikhshidids brought Egypt peace and prosperity by pursuing wise agrarian policies that increased yields, by eliminating tax abuses, and by reforming the administration. Neither the Tulinids nor the Ikhshidids sought to withdraw Egypt from the Islamic empire headed by the caliph in Baghdad. Ahmad ibn Tulun and his successors were orthodox Sunni Muslims, loyal to the principle of Islamic unity. Their purpose was to carve out an autonomous and hereditary principality under loose caliphal authority.

The Fatimids, the next dynasty to rule Egypt, unlike the Tulinids and the Ikhshidids, wanted independence, not autonomy, from Baghdad. In addition, as heads of a great religious movement, the Ismaili Shia Islam (see Glossary), they also challenged the Sunni Abbasids for the caliphate itself. The name of the dynasty is derived from Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad and the wife of Ali, the fourth caliph and the founder of Shia Islam. The leader of the movement, who first established the dynasty in Tunisia in 906, claimed descent from Fatima.

Under the Fatimids,

Egypt became the center of a vast empire, which at its peak comprised North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Syria, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Yemen, and the Hijaz in Arabia, including the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Control of the holy cities conferred enormous prestige on a Muslim sovereign and the power to use the yearly pilgrimage to Mecca to his advantage. Cairo was the seat of the Shia caliph, who was the head of a religion as well as the sovereign of an empire. The Fatimids established Al Azhar in Cairo as an intellectual center where scholars and teachers elaborated the doctrines of the Ismaili Shia faith.

The first century of Fatimid rule represents a high point for medieval Egypt. The administration was reorganized and expanded. It functioned with admirable efficiency: tax farming was abolished, and strict probity and regularity in the assessment and collection of taxes was enforced. The revenues of Egypt were high and were then augmented by the tribute of subject provinces. This period was also an age of great commercial expansion and industrial production. The Fatimids fostered both agriculture and industry and developed an important export trade. Realizing the importance of trade both for the prosperity of Egypt and for the extension of Fatimid influence, the Fatimids developed a wide network of commercial relations, notably with Europe and India, two areas with which Egypt had previously had almost no contact.

Egyptian ships sailed to Sicily and Spain. Egyptian fleets controlled the eastern Mediterranean, and the Fatimids established close relations with the Italian city states, particularly Amalfi and Pisa. The two great harbors of Alexandria in Egypt and Tripoli in present-day Lebanon became centers of world trade.

the Fatimids gradually extended their sovereignty over the ports and outlets of the Red Sea for trade with India and Southeast Asia and tried to win influence on the shores of the Indian Ocean. In lands far beyond the reach of Fatimid arms, the Ismaili missionary and the Egyptian merchant went side-by-side.

however, the Fatimid bid for world power failed. A weakened and shrunken empire was unable to resist the crusaders, who in July 1099 captured Jerusalem from the Fatimid garrison after a siege of five weeks.

The crusaders were driven from Jerusalem and most of Palestine by the great Kurdish general Salah ad Din ibn Ayyub, known in the West as Saladin. Saladin came to Egypt in 1168 in the entourage of his uncle, the Kurdish general Shirkuh, who became the wazir, or senior minister, of the last Fatimid caliph. After the death of his uncle, Saladin became the master of Egypt. The dynasty he founded in Egypt, called the Ayyubid, ruled until 1260.

Saladin abolished the Fatimid caliphate, which by this time was dead as a religious force, and returned Egypt to Sunni orthodoxy. He restored and tightened the bonds that tied Egypt to eastern Islam and reincorporated Egypt into the Sunni fold represented by the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad. At the same time, Egypt was opened to the new social changes and intellectual movements that had been emerging in the East. Saladin introduced into Egypt the madrasah, a mosque-college, which was the intellectual heart of the Sunni religious revival. Even Al Azhar, founded by the Fatimids, became in time the center of Islamic orthodoxy.

In 1193 Saladin died peacefully in Damascus. After his death, his dominions split up into a loose dynastic empire controlled by members of his family, the Ayyubids. Within this empire, the Ayyubid sultans of Egypt were paramount because their control of a rich, well-defined territory gave them a secure basis of power. Economically, the Ayyubid period was one of growth and prosperity. Italian, French, and Catalan merchants operated in ports under Ayyubid control. Egyptian products, including alum, for which there was a great demand, were exported to Europe. Egypt also profited from the transit trade from the East. Like the Fatimids before him, Saladin brought Yemen under his control, thus securing both ends of the Red Sea and an important commercial and strategic advantage.

Culturally, too, the Ayyubid period was one of great activity. Egypt became a center of Arab scholarship and literature and, along with Syria, acquired a cultural primacy that it has retained through the modern period. The prosperity of the cities, the patronage of the Ayyubid princes, and the Sunni revival made the Ayyubid period a cultural high point in Egyptian and Arab history.

The Mamluks, 1250-1517

To understand the history of Egypt during the later Middle Ages, it is necessary to consider two major events in the eastern Arab World: the migration of Turkish tribes during the Abbasid Caliphate and their eventual domination of it, and the Mongol invasion. Turkish tribes began moving west from the Eurasian steppes in the sixth century. As the Abbasid Empire weakened, Turkish tribes began to cross the frontier in search of pasturage. The Turks converted to Islam within a few decades after entering the Middle East. The Turks also entered the Middle East as mamluks (slaves) employed in the armies of Arab rulers. Mamluks, although slaves, were usually paid, sometimes handsomely, for their services. Indeed, a mamluk’s service as a soldier and member of an elite unit or as an imperial guard was an enviable first step in a career that opened to him the possibility of occupying the highest offices in the state. Mamluk training was not restricted to military matters and often included languages and literary and administrative skills to enable the mamluks to occupy administrative posts.

In the late tenth century, a new wave of Turks entered the empire as free warriors and conquerors. One group occupied Baghdad, took control of the central government, and reduced the Abbasid caliphs to puppets. The other moved west into Anatolia, which it conquered from a weakened Byzantine Empire.

The Mamluks had already established themselves in Egypt and were able to establish their own empire because the Mongols destroyed the Abbasid caliphate. In 1258 the Mongol invaders put to death the last Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. The following year, a Mongol army of as many as 120,000 men commanded by Hulagu Khan crossed the Euphrates and entered Syria. Meanwhile, in Egypt the last Ayyubid sultan had died in 1250, and political control of the state had passed to the Mamluk guards whose generals seized the sultanate. In 1258, soon after the news of the Mongol entry into Syria had reached Egypt, the Turkish Mamluk Qutuz declared himself sultan and organized the successful military resistance to the Mongol advance. The decisive battle was fought in 1260 at Ayn Jalut in Palestine, where Qutuz’s forces defeated the Mongol army.

An important role in the fighting was played by Baybars I, who shortly afterwards assassinated Qutuz and was chosen sultan. Baybars I (1260-77) was the real founder of the Mamluk Empire. He came from the elite corps of Turkish Mamluks, the Bahriyyah, socalled because they were garrisoned on the island of Rawdah on the Nile River. Baybars I established his rule firmly in Syria, forcing the Mongols back to their Iraqi territories.

At the end of the fourteenth century, power passed from the original Turkish elite, the Bahriyyah Mamluks, to Circassians, whom the Turkish Mamluk sultans had in their turn recruited as slave soldiers. Between 1260 and 1517, Mamluk sultans of TurcoCircassian origin ruled an empire that stretched from Egypt to Syria and included the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. As “shadow caliphs,” the Mamluk sultans organized the yearly pilgrimages to Mecca. Because of Mamluk power, the western Islamic world was shielded from the threat of the Mongols. The great cities, especially Cairo, the Mamluk capital, grew in prestige. By the fourteenth century, Cairo had become the preeminent religious center of the Muslim world.

EGYPT UNDER THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

In 1517 the Ottoman sultan Selim I (1512-20), known as Selim the Grim, conquered Egypt, defeating the Mamluk forces at Ar Raydaniyah, immediately outside Cairo. The origins of the Ottoman Empire go back to the Turkish-speaking tribes who crossed the frontier into Arab lands beginning in the tenth century. These Turkish tribes established themselves in Baghdad and Anatolia, but they were destroyed by the Mongols in the thirteenth century.

In the wake of the Mongol invasion, petty Turkish dynasties called amirates were formed in Anatolia. The leader of one of those dynasties was Osman (1280-1324), the founder of the Ottoman Empire. In the thirteenth century, his amirate was one of many; by the sixteenth century, the amirate had become an empire, one of the largest and longest lived in world history. By the fourteenth century, the Ottomans already had a substantial empire in Eastern Europe. In 1453 they conquered Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, which became the Ottoman capital and was renamed Istanbul. Between 1512 and 1520, the Ottomans added the Arab provinces, including Egypt, to their empire.

In Egypt the victorious Selim I left behind one of his most trusted collaborators, Khair Bey, as the ruler of Egypt. Khair Bey ruled as the sultan’s vassal, not as a provincial governor. He kept his court in the citadel, the ancient residence of the rulers of Egypt. Although Selim I did away with the Mamluk sultanate, neither he nor his successors succeeded in extinguishing Mamluk power and influence in Egypt.

Only in the first century of Ottoman rule was the governor of Egypt able to perform his tasks without the interference of the Mamluk beys (bey was the highest rank among the Mamluks). During the latter decades of the sixteenth century and the early seventeenth century, a series of revolts by various elements of the garrison troops occurred. During these years, there was also a revival within the Mamluk military structure. By the middle of the seventeenth century, political supremacy had passed to the beys. As the historian Daniel Crecelius has written, from that point on the history of Ottoman Egypt can be explained as the struggle between the Ottomans and the Mamluks for control of the administration and, hence, the revenues of Egypt, and the competition among rival Mamluk houses for control of the beylicate. This struggle affected Egyptian history until the late eighteenth century when one Mamluk bey gained an unprecedented control over the military and political structures and ousted the Ottoman governor.

As hard as may be to believe, there was an Egypt before the Pharaohs. Over a century ago, Charles Darwin, without any real evidence to back up his theory, set forth the statement that Africa might have been the cradle of the human race. Today, we still have no conclusive proof, but many signs point to one of the first civilizations created by human-like beings might have been in the Nile Valley around 700,000 years ago, if not earlier. Possible evidence to push the date back much earlier was found at Olduvai.

The Olduvai Gorge site in Tanzania is the oldest archaeological site in the world. Discovered by Dr. Mary D. Leakey and her husband, Louis Leakey, it contains the remains of large hominids (humanlike creatures) almost two million years old, which they labeled as Zinjanthropus boisei. But even more important than the remains themselves was the large amount of animal bones and crude stone tools found with them, evidence that these were intelligent beings. The existence of these stone tools prompted archaeologists to label them the “Olduwan Industry.”